Click

for Site Directory

Click

for Site Directory

I was recently contacted by a Mr John Waddington-Feather who is having a book published this year. As the book relates to WWII and barrage balloons he has sent me an extract to put on the website for people to have a taster of the work. He tells me the book will be published later this year.He writes:

See below for a sample from "Ira and the Hare"

Thank you

John Waddington-Feather

Press release. August 2006

Ira and the Cycling Club Lion and Other Short Stories.

by John Waddington-Feather

ISBN: 1 84175 240 1 Paperback. PP. 106 Price £5.99

Available from Feather Books, P.O. Box 438, Shrewsbury SY3 0WN, UK.

Tele/Fax (44) 01743 872177

or over the Internet on: http://www.waddysweb.freeuk.com

This collection of lively short stories began life as a series translated into Russian by the writer Dmytro Drozdovskyi, and published in the Ukrainian magazine, Porto Franko. One or two have Ukrainian settings, but most are placed around Keighley in West Yorkshire, the author’s hometown. The collection is a well balanced mixture of drama, sadness and typical Yorkshire humour.

………………………………………………………………………….

An Anglican NSM priest, John Waddington-Feather is a writer who belongs to the West Yorkshire ‘school’. Born in 1933 in Keighley, he attended Keighley Boys’ Grammar School and graduated in English at Leeds University in 1954. .

He now lives in Shrewsbury where he has ministered in the prison there for the past thirty seven years. He is a vice-president of the J.B.Priestley Society and a Life member of the Yorkshire Dialect Society and the Bronté Society.

Ira and the Hares

Ira lost his father at the age of four and his mother had been widowed twice by the time he was twelve. Times were lean in 1912 and Ira resorted to snickling hares on the moors behind their cottage to supplement their meals. He was a good poacher and was never caught, though he had some near misses.

Take the time when Billy Jackson, Squire Ferris’s gamekeeper saw Ira on his way home from the moors and guessed he had some snickled hares in his knapsack. A leathery-faced man, who looked as if he’d come out of the very soil, he’d been tailing Ira for some time and was determined to catch him red-handed. As Ira neared home, Jackson quickened his pace to overtake him, but Ira saw him and put some distance between himself and the older man.

As Ira topped the rise leading down to the cottage, Jackson yelled out, “Oi! Just a minute, young Fotheringill. What’s tha got in thi bag?” Ira shot out of sight and raced into the kitchen, hurling his hares under the sink, and stuffing a football jersey and boots into his knapsack. Then he ran out of the back door as Jackson came puffing up.

“Come ‘ere, thee!” shouted the gamekeeper, grabbing Ira by the collar. “Ah know what tha’s been up to. Let’s look i’ thi bag.”

Ira came the innocent and put on a hurt look. He handed over his bag, saying, “There’s nobbut mi football kit in there, Mr Jackson. Ah’m off laking football in t’village. Tha can come an’ watch us if tha wants. We need a bit o’ support.”

Jackson glared at him then opened the bag and shook out its contents. Having examined it, he threw it to the floor with snort. “Yer little bugger!” he growled. “Ah’ll catch thee yet. Then tha’ll be for t’high jump good an’ proper. Squire Ferris’ll have thee sent away to t’Reformatory School. Thee mark my words! I’ll have thee yet, yer young bugger!”

Ira waited till the gamekeeper was at a safe distance before yelling after him, “Mr Jackson! Does tha know what to do when tha catches a weasel sleeping?”

The other turned and asked, “What?”

“Piss in his ear!” grinned Ira, then fled before the gamekeeper could reply.

He never was caught and he and his mother lived well off the game he poached till times got better; leastways till Ira started work and more money came in. Times never really got better for years – not until after two world wars; not until the end of the century.

Ira served in both wars, joining the Royal Flying Corps as a volunteer in 1917 as soon as he was old enough to join up. He survived when many of his school friends were killed in the trenches, including most of the village soccer team he played for. Jackson, the gamekeeper, was also killed on the Somme. Life was never the same and Ira never snickled hare again for years – not until the Second World War in 1940. By then he was over forty.

It was like this. The second time round he was drafted into a Barrage Balloon Squadron. They thought he was too old to do much else and Ira also thought he was onto a cushy number, till he began training. Being a much older man than the others, his basic training left him almost crippled with bad feet and he was off duty for some days.

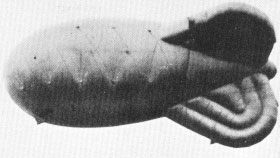

When he resumed he became part of a balloon crew, ten men in all, who serviced and maintained the huge balloon, its winch and moorings and the lorry to which it was attached, making sure the unwieldy thing got airborne and stayed in place. Its purpose was to form a barrage, a shield, with the other balloons to keep the German bombers flying high and stop low level raids.

The balloon crew were also trained to use anti-aircraft guns and rifles. Ira discovered why when the crew had their first taste of action. At first it wasn’t so bad in 1940, during the phoney war period. The air-raids hadn’t started and the balloon crews had an easy spring and summer, swanning round the country practising flying their balloons in calm, sunny weather. Later, when freezing winter gales blew in, it was quite another tale. Their balloon became a living beast, bucking and threshing uncontrollably like a mad thing on the end of its cable.

They dreaded the heavy cable snapping. If it did, they knew what to expect when 1,000 metres of it came crashing down with enough force to cut a man in two. And if the balloon broke free, its trailing cable played havoc with rooftops and chimneys. It was designed to bring down aircraft and could saw off a whole wing if one flew into it. In one gale a score of balloons broke free and finished up in Sweden!

If a balloon broke from its moorings, they had to put up a fighter to shoot it down; and the German fighter pilots also cottoned on to this when air-raids began for real. They’d fly in ahead of the bombers to gun down the balloons and put out the searchlights.

Ira’s crew got on well together. They’d all done basic training, shared the same billet, shared the shock of leaving civvy street and becoming servicemen. There was Bill, Jack, Harry, Geraint, Sam, Ernest, Neil, Herbert, George and, of course, Ira. They were like one big family with Ira as their dad. They came from every part of Britain and from every background.

They had their first taste of Jerry one night when they were sent to the south coast to ring an airfield. They’d just settled in and were clearing up their billet when the alarm went off and they scrambled outside. The sky was full of anti-aircraft shells and machine-gun fire. Searchlights stabbed the black sky feeling feverishly for the enemy aircraft. Several balloons, including their own, were already coming down in flames.

Balloons were being hauled down as fast as their winches could take them, as German fighters hurtled down raking the balloon and searchlight sites. “Behind you!” yelled Ernest, the corporal, as a Messerschmitt 109 came roaring in dangerously low from the rear. The gun crew swung their weapons round as the fighter’s shells spurted all around them. Then he was over them and gone. He turned and banked, as if to come in again for another sweep, but even as he hung, for seconds it seemed, the balloon crew hit him.

The Messerschmitt dipped suddenly and continued out to sea trailing smoke. Then it vanished from the beams of the searchlights. Later, the body of the pilot was recovered from the sea.

When the Germans switched their attacks from the airfields to the cities, Ira’s flight was on the move constantly, going from air raid to air raid as the German radar code was cracked. It was while his flight was on its way north to Sheffield that Ira began snickling hares again in the flat acres of the Midlands.

They’d stopped temporarily on the edge of a large farm and set up camp to check out their equipment and rest. The convoy was parked on a slip-road next a farm and had a good view of the nearby fields. It was early spring and the meadows were full of hare. Ira ran a practised eye over them and noted their runs. With any luck, they’d have fresh meat for lunch; a welcome change from the canned meat they’d been eating for days.

All was peaceful and still. The skies were open and clear, the fields just beginning to green in the first hints of summer. A skylark got up not far away and began pouring down his torrent of song. It was so peaceful and utterly rural, a world away from the carnage of war.

Once they’d finished checking their lorries and balloons, Ira set off with a couple of newly made snares. It was almost thirty years since he’d last caught a hare but there was no gamekeeper to be wary of this time. He was a lad again and back within the hour with a brace of hare.

He’d only just returned when the flight sergeant said they’d be on the move in a couple of hours and to report to him for briefing. “You stay here,” he ordered Harry Black, the youngest of the crew, “and keep guard. We don’t want anyone pinching our petrol.”

“Can you skin and cook these?” asked Ira pointing to the hares before he left.

“’Course I can,” said young Harry. “Seen me muvver do it scores of times.”

“Then get them in the oven double quick,” said Ira, hurrying off to join the rest of the crew.

In the break from the briefing, Ira dashed back to see how Harry was faring. He noticed the hares’ skins, but also a terrible stench coming from the camp-oven where the hares were roasting. He sensed the worst!

When he opened the oven doors, there staring back at him, skinned all right, but with their heads still on and ungutted were the two hares. The stench was unbearable as Ira fished them out. Fortunately they hadn’t been in long enough to ruin them. He cut off their heads at once and gutted them before replacing them in the oven, retching all the while. What he said to young Black can’t be repeated, but when he returned to the others he said nothing – nor did Harry Black.

By the time the rest of the crew returned hungry the hares were well done and smelled appetising – except to Ira. Their old smell still lingered in his nostrils. The crew tucked in with zest but Ira had canned beef that night. Once they’d eaten they were off in a long grey convoy heading for Sheffield.

They reached their destination at dusk and winched up their balloons around the railway station. As night set in and the city blacked out, an ominous silence fell. The streets were empty devoid of people and traffic. Then, about midnight, the sickening drone of German bombers and fighters came over the horizon, distantly at first then growing in volume as they came nearer and nearer.

The night was clear and they saw them approaching like black birds of prey swarming across the sky. The night burst into life as searchlights probed the sky and a thousand ack-ack shells burst. They could see their balloons, elephantine silhouettes etched under the bombers. Then the fighters peeled off to take out the balloons and searchlights as the city burned.

Ira and his crew struggled to keep their balloon aloft as the bombs rained down. He was winching on one side of their lorry and the rest of the crew on the other when it happened. A stick of high explosives straddled the railway station. An engine and its tender spun disintegrating in the air like a toy. Then the blast caught the crew. Bill, Jack, Harry, Geraint, Sam, Ernest, Neil, Herbert and George were blown to bits. The lorry and Ira were lifted metres down the road, the one burning fiercely, the other lying badly injured and burnt.

Ira spent months in hospital. His wife, Belle, barely recognised him when they removed his bandages, but he lived another thirty years, held together by a metal corset and kept alive by drugs – and Belle. He recovered enough to go drinking at his clubs, but he was never the same. Later, he and Belle moved to Shropshire near his son, where he died peacefully enough, unsung and forgotten in Keighworth.

To snickle = to snare. (Northern dialect)

To lake = to play (Northern dialect)

Nobbut = only (Northern dialect)

Cushy number = an easy option (slang)

Swanning = roaming about (slang)

Reformatory School = young offenders prison.

Civvy street = civilian life (Army slang)

Ack-ack = anti-aircraft guns (Army slang)

Jerry = Nazi forces (Army slang)

Muvver = mother (Cockney dialect)

John Waddington-Feather ©