Click for Site Directory

Click for Site Directory

How

My Sister Won The War By Alan Rimmer

My sister, Leonora, was only sixteen when she joined the WAAF in 1941 and became a barrage balloon operator. She did this until 1945.

At the end of the war, she went to Egypt where she did clerical work associated with the demobilization of troops that came there from

various countries to the east. She was demobilized in 1947 at the age of twenty-two years, having been six years in the WAAF.

Most of what is reported here is taken from tape recordings my sister made for

me when I expressed an interest in writing of her war experiences.

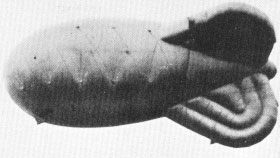

Operating a Barrage Balloon was anything but routine. There were well established procedures describing how to go about the operation and

maintenance of a balloon but there were always variables which created serious departures from normal routines. The number of girls in the

crew was one of the variables. The fewer the number of girls, the more work that had to be done by those who remained. Perhaps the biggest

variable was the weather followed closely by enemy activity.

"It seemed that all the nasty things happened when the weather was rotten. When we had to bring a balloon down because of weather, if it was

very severe, then we would have to storm bed it, which meant bringing it down until its belly was on the ground and tied down all the way

around. Of course, when it was down that way, you still had to move it and keep the bow into the wind. So, in the pouring rain, the wind

would shift, and we had to get out and drag those heavy concrete blocks, and undo the ropes, move them around and turn that balloon into wind.

Before you got it into that position, those fins that are at the rear of the

balloon had to be furled.

"The balloon is thirty feet high and the ladder is very tall. Two girls had to hold the ladder and, of course, being the tallest girl, I had to furl

the fins. I would let the air out of them, and then roll them up. It would be raining, and the rain went down my sleeves, down the back of my

neck and everybody had chapped hands. I had chapped arms, chapped elbows, and all these little cuts. Miserable! The ladder would be shaking,

and they would be hanging onto the bottom of it and the balloon would be banging up against it because of the wind; it would he pitch black.

I could use my awl to do a lot because they had slipknots that would undo very quickly when we had to release the balloon again.

That was one of the most unpleasant jobs.

“There was nothing related to the maintenance of a balloon that was good to do. It was all dirty work; dirty oil ...your hands... I never took

off my gloves if I could avoid it. I would have all this old engine oil under my nails. There was not a way you could get it out. Then if you had

cuts on your hands and up your arms, they would get oil in them. You just looked

scruffy alt the time you were handling a balloon.

"There was one site I was on. I cannot remember where it was exactly, probably Stoke Newington, but it was on a park because there was

space, and it adjoined a lumberyard. We had a serious storm with a lot of rain and a lot of lightning and there was also an air raid alert on.

Our balloon caught fire and went into the lumberyard. I don't know whether the lightning got it or it was shot at, but it went into the

lumberyard and started a fire there. That was one night. We had just cleared up that thing and we lost another one. We got the other one

inflated and got it up a couple of nights later and that broke loose.

“The cable was dragged across a Held, over the railway

tracks, into the town. Now, all the cable was out with the balloon. I cannot

think

how it happened as the flying cable is supposed to break free. It might have been shot down because it started to deltaic or, perhaps, the

wind had been too much for it. The rip panel had gone but the cable had not broken, and it had gone all the way across the railway

embankment, across the park, into the town, over the trolley lines. It knocked out all the power at 6 o'clock in the morning in the

pouring rain.

"It was back into the gum boots, and the rain gear, and

we started following the cable. We saw that where it has gone over the

railway

embankment; there was a tunnel that led into the town. We knew we had a dangerous situation and, sure enough, the early morning train

came along. The train picked up the cable. We all realized what was going to happen. It was going to be pulled along and then it would

whip across, which is exactly what happened, so we all ran in one direction and the cable, when it was caught by the train, went in

the other direction, and just scythed out the whole victory garden that was in

the park. It cut everything off. “

“The train just went on. We followed the cable and sang. ‘Follow the Yellow Brick Road’, as we went. We went into town. They were

pretty mad at us, all these people standing on the street corners, and the balloon had come down in the railway station yard. It was just

lying there, all deflated, and the first thing we had to do was to get all the secretive stuff off, the valves and any other thing that nobody

should see. We then cut the cable into sections. We had been doing that on the way over there, with a big cable cutter, and coiled it up.

We took the balloon, hauled it and put it all in this wheelbarrow and push it back to the site. Of course, there were all these people

standing around without a trolley bus to take them to work and yelling at us.

'It's not our fault!' we said.

“While we thought it was really funny, they didn't think it was funny at all. We took it back and called headquarters. They sent out another

balloon. We lost two in about ten days.

"They then moved us down to the dock area in Wapping,

Whitechapel, Elephant and Castle and Stepney. Not the nicest parts of

London.

The docks were not too far away, and we had a Nissen hut and a wooden hut, an above ground air raid shelter, an Anderson shelter, an

underground shelter on the site, and a balloon. The balloon (I think it was a dog site) did not fly an awful lot but it could fly in there.

There was enough room for it. But the regular bombing was very heavy. They were still lulling the docks and they would knock out some

of the tenements. It was bad. It was dangerous because there was constant bombing. It was mostly at night. During the day, the V-1's would

come in. These were the first of the flying bombs. They were called buzz bombs or doodlebugs. You could see them coming in. We would

stand outside and watch them. There might be two or three. One would be going off to your right, one to your left and one coming at you.

You would watch to see which was going down first and where it was going, and

then you would make a run for the shelter.

“Many times, the engine would remain on and it would come

in like a dive-bomber with a terrible noise as it came in. It was much

better

if the engine shut off: it was not noisy that way. You would get the hang of it at the end, but that screaming noise of the plane coming

down was pretty hard to take. But the buzz bombs were thick. I remember one time, we counted eight all at once coming in. Then at

night they had the regular bombing raids. They kept us busy. We slept in the shelters. That was the first time I actually slept in the shelter.

I slept in the surface shelter; I did not like going underground too much. But we had a good surface shelter that had bunks in it. In any case,

the Nissen Hut got bombed. We couldn't sleep in that anymore. We would normally sleep in the Nissen Hut and would go in the shelter

when the siren went off.

(c)

Alan Rimmer 2019