Click

for Site Directory

Click

for Site Directory"For the Duration" the war time exploits of L.A.C. D.J.Roberts, 1940-1945 (BALLOONS)

Having received my Calling up papers I left home on the morning of Thursday June 13th 1940. I had volunteered only a week previous selecting the RAF and I was surprised to be called so soon.

I felt far from happy as I said goodbye to Glad but the die was cast - dressed in my blue pin stripe coat flannels, Raglan and carrying a small case holding a few necessities, I kissed her goodbye and

made my way to the Market Place to catch my bus to Wigan - and a journey that was to keep me from home for periods over 5 years. At Wigan I met up with forty other chaps all prospective

Airman, and we were split up into

two parties. I being put in charge over one party and given Route forms and fare to

take us to Padgate,

We

boarded the train, it was obvious to passers by we were on our way into the

Service and many cheered us along with well wishes. By the time we reached

us were on speaking terms - until we entered the gates at Padgate where we were met by a RAF policeman.

He seemed to an instant dislike to us all. "Stop talking" he bawled "and follow me! I don't expect you to MARCH but keep together and donít get run over!".

Well that was the start we shuffled along trying not to look self conscious. Anyhow our first issue was a knife fork and spoon and mug and we were given a meal, after that we drew bedding, were

given sleeping accommodation and after being warned to be on parade 08.00 hours we settled down to our first night. First night, I shanít ever forget that, sleeping alone after seven years

married life and trying to realise that this was to be our lot for the duration, some chaps were talking quietly, others I noticed just lay gazing at the ceiling, a chap from Wigan raised the last laugh

by

looking under his bed and exclaiming indignantly "What: No Pot!" and

then to a chorus of Good nights we doused the light and tried to sleep.

fair, but we felt uncomfortable being the butt for many laughs from chaps who had got their uniforms and who looked at us with disdain. After breakfast we "paraded" on the Square and were

taken by a Corporal to the Station Headquarters where we hung around until our names were called. When it came my turn I went into the Orderly Room where they took all particulars and told

me I was, as a prospective Balloon Operator liable for immediate service.

In the afternoon I was, with others sworn in to "Fight and

protect the King, his heirs and successors etc etc. So help me God".

After that things moved fast and on the Saturday we were led into a large hanger full of clothing and equipment and given a kit bag, which as we moved along it was like "Woolworths': help

yourself cafe". It rapidly became full of items of equipment and clothing, our uniforms were fitted by a tailor who just paraded us, and as he walked along and passed each man shouted a number

(this size) and woe betide the man who forgot it. Still I must admit he was good. Back to the billet we staggered to discard our Civvies and don uniform, it was surprising the difference it made to us

all.

I hardly recognised myself in the mirror, to get the forage cap to stick on my head was a problem for days. Anyhow we felt as if we belonged to the R.A.F. now and as we marched along in our

squeaky boots - we even tried to keep in step!

One thing amongst others I learned at

seven of us were posted to

went to No.14 Balloon Centre at Ely for our course. There was little accommodation at the time, and we had to go under canvas, still the weather was good and except for the earwigs, and beetles

that took great delight in dropping on us! Once in bed, it wasnít bad.

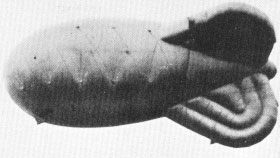

Here I saw my first barrage balloon at close quarters, and began to learn about it in theory and practice it was obvious they couldnít train us quick enough and Jerry was coming over

every night and most of our docks and cities were open targets, they kept us hard at it, after some days we were sent to civilian billets near the camp. I was lucky enough with a pal to get with a

Mrs. Rockett,

enough many a time.

I couldn't afford a stamp. Glad was feeling the pinch as well, her letters were getting more depressed, she blamed me for joining, all of which worried me. One day we were surprised when told to

leave our digs, pack and

prepare for a move and in the afternoon we formed a convoy and started out for

Barry docks. It all seemed very urgent and most of us

was hammering the dock every night, so we didnít feel very optimistic. On arrival at Barry we ate and slept at the Masonic Hall sleeping on the floor, but we were up at 4 a.m., and split up into

crews, detailed to our sites and told to have our balloons flying for 8 a.m.!

I was unlucky enough to get on the

entailed much graft from all of us. Food had to be forgotten - we had nowhere to sleep, the balloon was the only thing, the Dockers watched us keenly and even helped at times, and at precisely

8 a.m. the result of our work at a given signal lifted itself slowly and flabbily into the cold morning air, all around we could see its future companions and given a lead by the Dockers, we cheered.

It wasnít a very thick barrage but its morale effect on the townspeople was obvious.

The rest of that day was spent erecting our two tents, food was brought by the Despatch Rider, badly mashed, but welcome, near us were billeted some elderly soldiers (the old Local Defence

Volunteers-later renamed as Home Guard.) who were doing guard duties, they helped us a lot and even supplied us daily with a rum ration - which they were supposed to guard.

It proved to be a rough life but we were a good balloon crew, just eight of us and one Corporal, my closest pal was a chap named Pollock ,in civilian street he had been a commercial traveller, he

didnít care for the heavy balloon work.

Life was made up of squadron duties two hours on four hours off day and night, in between we had to rope splice. maintain the balloon, the winch and site. The air raid siren seemed to be

continually blowing at night time, being worst of all promptly at 10.00 p.m. They would blow it and shortly after we would hear the drone of aircraft. Our only defence, apart from the Barrage

Balloon were a few anti aircraft guns mounted on the ships. Jerry seemed to know that we had poor defences and after circling overhead would send down his load of "screaming" bombs, we had

only a slit trench for shelter

in which we would lay and pray.

One night I can never forget, I was on guard, the air raid was becoming intensified and the Corporal had ordered me to stay on the site and take refuge under the winch if necessary. He and the

remainder retreated to cover. I was to watch the cable the balloon being hidden in the black night. I lay under the winch wearing my tin hat, clutching my rifle, every bomb seemed to get nearer,

and the shrapnel from the Anti-aircraft fire was even dropping on the winch above me. Suddenly I heard a sound like an express train rushing out of the heavens, I suppose I just panicked, I know

I jumped up and ran towards the slit trench, as I reached it I realised everywhere was lit up like day, I could see the cranes, buildings and shipping - from behind me came a terrific crash - I

seemed to be picked up like a straw and dropped again as suddenly. I lay where I fell, while over my head whistled wagon wheels, earth and God knows what. I lay my face buried in the earth,

after a few seconds except for an occasional fall of glass from broken windows things became quite, deathly quite, it seemed. I stumbled to my feet and made my way to the trench and fell almost

into Pollocks arms, he was weeping; "What's wrong with you?" I panted. "Its you Robby!", he said "I thought youíd had it!"

To say I was badly shaken, would be to put it mildly but I was unhurt. I remember the Corporal running around the site in the dark calling my name. I took a great delight in being slow to

answer, but when he saw me alive and unhurt his relief was genuine. He had himself been sheltering in a large concrete shelter belonging to the London, Midland and Scottish Railway.

ruined, railway lines were just torn up like paper and one of a line of wagons had just disappeared. Our Commanding Officer came and was quite concerned.

Still that wasn't the only adventure, one tea time we had started tea the table being laid in the open owing to the hot weather. The sirens had gone and we knew a plane was around. Suddenly the

orderly who was pouring out the tea looked up as we heard the roar of Aero engines, "Jerry!", he yelled. I looked up over our head not 200 ft up roared a Junkers 88 we could see the markings,

the pilot and everything, once immediately over our heads he seemed to open up his guns, bullets flew like angry flies across the site, luckily no-one was hit. Over went the table and everything

on it, the Corporal roared for us to load our rifles, in case he came back but it wasnít necessary as if by magic a Spitfire appeared, he only seemed to give the German one burst and with a mighty

roar he dived into the sea, we cheered like a football crowd, it was the first Jerry I saw finish up in the Bristol Channel but not the last. I saw one crash into the scenic railway and burn like a

firework display at

and safety of

us they were never hit but I

heard shrapnel and machine gun bullets rattling across them like hailstone.

supposed to fly the balloon until the

position became hopeless then sabotage the winch and then commit Hari Kiri I

suppose!

Round about Xmas 1941 was the worst time South Wales had

pieces on the

hard to make her realise the sort of life we were leading and the laughter of the people at the other end of the wire made me realise how little the North knew of the sufferings of the people in

the Target Areas.

coal dust and took a liking to company of the big ships which lay alongside Dutch, Norwegian and others. Leave started in August 1941, and soon after I got home for my first seven days and at

other times, for 48 hour passes. Often I overstayed - thinking of the misery of service life, of course I had to pay and I found myself often on the carpet and as a result confined to the site.

I was now an Aircraftman 1st Class Balloon Operator, which made my pay more presentable, also we had been given a 6d. a day increase (cigarette money). A training site was formed at this time

actually it was a Rest site. The Billett was near Cadoxton Sanatorium, green fields clean air and a smell of the sea and I felt the benefit. I moved there with my pal Jack Mundy who was enraptured

by it all after the filthy dock site.

The day we arrived there we made our beds and were awaiting dinner. Mundy decided to wander down to the beach which was quite near, he asked me to accompany him, but I declined being

more interested in my dinner. So whistling for the dog he left. We had finished eating and were sitting back smoking when we heard the explosion! It startled and puzzled us all, no-one could

decide what it was, I suggested it was one of the guns from the fort but the Corporal said it was too near, then, when the dog came back barking and looking very distressed the Corporal decided to

investigate and left with three men. I didnít go. They werenít away long and returned pale and shaken. "Its Jack Mundy, the Corporal said "Heís been blown up by a mine." We found his head and

shoulders in the trees."

Well, I know that was the greatest shock of my life. I couldnít realise it, not twenty minutes previous he had been beside me full of life. An inquest was held of course and a verdict of accidental

death returned. We all knew the beach was mined and fenced off, how or why he trespassed will never be known, his curiosity cost his life. He left a wife and several kiddies. We buried him with

Military honours in

The grave and headstone of 927298 Aircraftman 2nd Class AUGUSTUS CHARLES MUNDY, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve Unit 969 Balloon Squadron.

Date of Death: 12/04/1941 at the age of 33.

Commonwealth War Dead Grave/Memorial Reference: Sec. R. Grave 1308.

He was born in January 1908 at Amesbury and was the son of William John Mundy, a Farm Labourer and Martha Ann Mundy (nee Dicks) of Orcheston St Mary, Wiltshire.

He had had married one Olive G. A. Mundy (nee Bartlett) in 1933 at Warminster.

A diary kept by Fl/Lt Edward Hall who was adjutant of 969 Squadron reveals that the circumstances surrounding his death were far more disturbing.

(It appears that he had been a bit strange before his death and had taken his family to a local photographer and posed with them for photographs, for the first time in his life. He then made

specific instructions as to how his favourite son was to be cared "if he was killed". in addition he stated that he hoped he would go "all at once".

The diary records that Jack Mundy must have committed suicide because while based at Hayes Farm, he had ignored several signs, clearly displaying a warning of mines, as well as getting over

two difficult and separate fences to keep people out of the minefield. It appears he was then seen to have jumped onto a mine in the sand which exploded causing the adjacent mine to explode as

well. His body was scattered over a wide area in a perfect circle and was not accessible due to the mines. The diary comments on the fact that in order to have a funeral they would have to enter

the minefield and recover the body parts but his head was in a barbed wire entanglement. It appears that Mrs Mundy was unaware at the time of the fact that his death was likely to have been a

premeditated event. Somehow his remains were gathered up for burial. It appears that Mrs Mundy, her son and her sister-in-law came to Cardiff for the funeral. Fl/Lt Hall comments that Mundy

little cared about all the work his death would cause for the adjutant of the squadron.)

I didnít stay on this site after. I asked to be sent back to the docks, and there I stayed through the following winter. The weather proved to be our worst enemy. We lost practically a balloon a

week as a result of the gales which swept up the channel. Many a night we have fought through the rain and wind to save our Blimp, like the sailing men of old. Balloon work at this time was just

manual labour and cannot be compared with procedures used later, when months of practical experiments resulted in much easier handling. So making it possible for W.A.A.F. (in fair weather) to

do the work. About this time Waterbourne balloons had been installed in the channel and when they asked for volunteers, I put my name down. I went to sea a few days later, our home was a

fishing drifter manned by four Belgians and belonging to the Belgian fishing fleet who

came over here when

These boats tossed like corks being two light for the yawing of the balloon when flying, so that even the Belgians complained, still we had to stick it. I had only been out there four days, the

Germans started sowing their magnetic mines and the Admiralty were in a panic to counteract them still they weren't long and the "wiping" or de-gauzing of ships started. On inspection they told

us it neednít apply to our ships as they were mostly wood and wouldnít attract the mines. We proved them wrong on the fourth night. I was in them. Not our drifter but another not far away.

disappeared one night in loud explosion, all were lost but one and the Corporal and I heard afterwards it would be unlikely if he ever walked again. The result of this was that we were sent

ashore again, and I wasnít sorry. Although the

drifters did put to sea again I wasnít detailed and stayed on land for the

rest of my time in Barry.

I then heard the sad news that my mother was seriously ill and I was given leave to see her, she lingered while I was on my seven days leave, but died two days after I got back so that I had to

rush home again, this tragic business over, I was told I was posted near home under the repatriation scheme, glad I was when the day came. it was with sad thoughts that I left Barry, we had

worked hard there, and the people knew and appreciated us, so with a

general hand-shake around and a last look towards the little cemetery on the

hill, I boarded the train for the North.

My Route form told me I was posted to Runcorn 122 Squadron with Headquarters

at

night, they refused me permission to go home, although from the hill on which the castle stands I could see the slag heaps of the collieries right near home. Next day I was taken by van to my new

site which was a Rugby field and pavilion beside the canal and right near the locks. (it seems I was destined to stay near water). I found that the majority of the crew were local auxiliaries mostly

from Warrington, and I was elated at the prospect of getting home as often as seemed possible. Still, it proved that Gladys and the two girls came to see me first, a telephone call one day from

Headquarters told me they were on their way to the site and I spent the afternoon with them in Runcorn.

During my stay there I was able to get home at least once each week and after Gladys visited me, I was persuaded to take the job of site cook about this time, this system having just started.

I didnít start so well but in time became quite efficient and remained cook for many months, after the hectic life of Barry Docks this was like convalescence. I only remember one raid while I was

at Runcorn. Still it was to good to last. W.A.A.F.s were being recruited into Balloon work, as I said before. Balloon handling, owing to suggestions and mechanical modification had become much

easier and the result was men were being posted away to danger areas. They decided to move Volunteer Reservists first and one day I was given two hours notice to pack. Within three hours I was

on Warrington station ready to move South, I had been given no time to

warn Gladys and though I searched Warrington station I couldnít see anyone

from home. Our destination was

there must have been nearly five hundred of us.

We arrived at

sent for) took us to the Drill Hall, we arrived about midnight no one seemed to know we were coming, cooks and clerks had to be got out of bed, they gave us blankets only and after a cup of

coarse coffee and

some bread and cheese, we bedded down on the dance floor - so this was London

!.

to be Dagenham and a site just of the main road. The first thing that shook me on our arrival wasnít the bomb damage or Fords great works - it was the magnificence of the billett I was to sleep in,

it was just the usual Air Ministry style but internally it was spotless, the floor was polished like glass, the walls cleanly painted, the stove was obviously never used, but shone like ebony on it

stood a bowl of flowers. The site cook dressed in immaculate whites asked me if I had had dinner. I answered No, he immediately prepared one and while I had had dinner, he gave me all the gen

from then on he was my closest pal, his nickname was ďCurlyĒ he was completely bald, thought a comparatively young man.

The rest of the crew all Londoners were pretty decent. There were two Corporals it was obvious the discipline down here was keener and spit and polish seemed to be more important than

balloon work. I found that so, all the time I was in

Still I managed to fit in and in spite of all the glamour, I soon found I was

under Jerries attention again. Just beside our site on the

great morgue with forty or fifty grim concrete slabs. Well I stayed there long enough to see most of those slabs occupied. I shanít forget the day when the old attendant gave me two shrouds to use

as bed sheets, "I supplied all the other lads" he said. Sometimes the raids were heavy, then there would be comparative quite light. Jerry did ruin a quiet game of Monopoly one afternoon by a

Dornier roaring right over the billet and dropping his bombs intended for Fords, harmlessly on the marshes. We were right near the great housing estate and during one raid the nearest house to

us was wiped out, we were luckily in the shelter, the woman in the house was killed instantly she had no relatives, Her husband was serving abroad and a week after the tragedy the postman

called around to say that her husband had been killed in action. Still life for us went on, at times between leave it was very monotonous, except on my 48 hours off I visited the City and made

myself acquainted with most of the places of interest. Apart from balloon work here, we were taught street fighting and did lots of marches and range firing. The war position was still serious but

the Battle of Britain was swinging in our favour, still the word "Abroad" was something to make one uneasy. We took solace from our worries by drinking hard and often in the old "Ship and Shovel"

where we sang loudly if not lyrically. But it seemed I wasn't to settle for long. My Nemesis was the W.A.A.F., it was decided that they should take over some sites, ours was included and it wasn't

long before the Works and Bricks Dept were erecting the extra hut and etc to house the sixteen W.A.A.F's.

We were asked to volunteer for river work and the site volunteered "en bloc" so we left the women to their playground, we even made their beds before we left and they looked pitiful as we

climbed into wagons to leave. I

think they thought we were to work on a 50-50 basis, the idea of being left

alone with everything left them badly shaken.

doing a sort of bring and carry job. The crew were civilians, well, four of us were lucky enough to get on the same barge, the other being shared equally on the adjacent craft. Actually there were

two barges moored side by side to two huge buoys, in peacetime they had been sugar barges, their size can be judged by the fact that the balloon and winch could be held in the hold of one,

when the balloon was bedded down it entered the hold completely only the top showing, the second barge acted as living quarters and galley, both being below water. ďCurly" whose reputation

had proceeded, him was nominated as cook immediately, we inspected our bunks it was all shipshape and plenty of room, our Mae West we used as pillows (and in case). The one snag was the

damp from the condensation, causing the sides to continually drip water. We were only in touch to land by the Radio Transmitter set being about lĹ miles offshore, between Barking power station

and Woolwich Arsenal. The Corporal in charge and old river man gave us instructions and advice, never wear boots he said, always slippers, get familiar with the deck, (the deck being two feet

wide, on the balloon barge) and don't take chances. Well I soon found how dangerous it was just the two feet wide deck to run around, ropes to be avoided and undone, ballast bags to detach and

all the timethe balloon like some captive elephant trying to free itself from the hold and push us overboard. Night-time would have tried the courage of the hardest, once over the side and into

rushing black stream and you were lost, Still, I got used to it, as I got used to the pitch of the barge while in my bunk at night, listening to the crash and rattle of the mooring chains and the sucking

sound of the water, the sudden roll of the barge as some huge vessel passed us. I had many experiences on the river some funny and some pretty grim when I think back. To get the food supplies

we had to board the launch which did a round trip and we collected the food from the nearest land site, but often in good weather we used the dinghy ,with two us rowing, we could make it quite

easy. I got to like the the experience and the physical feeling of well being it gave me and took every opportunity of rowing ashore whatever the errand. One trip we made was the laugh of the

river for days owing to our inexperience. Having tied up the dinghy we stayed at the land site longer than usual so that it was dusk when we got back to the jetty. I climbed down the steep ladder

first, when I got the suprise of my life, feeling down with my foot for the dinghy, I found it alright but instead of floating on the painter it was hanging in mid-air. Yes the tide had gone out and like

the landlubbers we were, we hadnít allowed enough rope, after much manoeuvring we righted it and got back safely. Another instance which happened in our earlier days wasnít quite so funny,

to me anyway, I believe it was our first trip returning to the barge and making for the ladder I slipped my oar and made to catch the said ladder, Instead of my pal directing the dinghy upstream a

little way and then drifting back to it, he made straight for it so that as he stopped rowing and I reached for the ladder the fast stream pushed us past it. I missed and fell overboard, luckily on

coming to the surface, I managed, in spite of being a poor swimmer and the weight of my clothes, to keep afloat until I caught hold of the dinghy, I wasnít much worse for the mishap except for the

water I swallowed, but the Corporal gave us both a good lecture. Anyhow my baptism made a real river man of me, I had something to bray about, I probably crammed more incidents into my river

life than any time afterwards.

terrific, pots and pans from the galley, shelves crashed to the floor, the wireless fell in smithereens, the hanging lamps swung like swinging boats, we staggered up the steps towards the deck,

and when I saw the bows of the huge collier towering above us like the local town hall I nearly fainted. In the dark and the fog it was impossible to see what damage been done, anyhow none of us

would have had the guts to jump overboard, there was much shouting and flashing of lights. Anyhow we didnít sink, the external damage was negligible, and for the interior the company were

forced to pay, So we were received a new wireless and new crockery and other comforts we'd never enjoyed previously as compensation. Sometimes the fog came down for days, once it lasted a

week, no one could get to us, we ate all the emergency rations and we were in a pretty bad plight for drinking water, when some of us volunteered to row to the nearest land barge for rations,

they managed to contact shore during a thinning of the fog.

It was a trying experience rowing in the fog as we left our barge our Corporal banged on a gong continually, as the sound of this grew fainted we listened latently for the sound of the gong on the

other barge and headed towards it, it wasnít easy, sometimes they were ahead then to our port or starboard but when we got within shouting distance and could Ahoy each other it was different,

still the trip which normally took about ĺ of an hour took about 2Ĺ, it was eerie and dangerous, Iím sure we didnít realize all the dangers, but hunger compelled.

My nearest pal at this time was a little Scotsman named Jock Lorie, we were destined to travel far together, and while on the river we spent our periods ashore together usually at Barking or

Ilford, sometimes going up to London, the river police were frequent visitors and good friends, especially A. P. Herbert the author and M. P., who was an auxiliary Sgt he promised to write a book

someday giving details of our lives. Raids were frequent as usual, being on a barge in midstream may be some peoples idea of safety, it wasnít mine, the bombs many times fell in the river near us

sending up huge geysers of

water, shrapnel rained down, we were just sitting ducks, nowhere to run, on

deck it was dangerous, below it was impossible to see when danger approached.

Still we carried on and liked it, "rumours" from Headquarters, were numerous, one being that, mobile Balloon Units were being formed as Jerry had attacked Canterbury, an open city and

others undefended were threatened. This "rumour" proved true anyway, and it wasnít long before Lorie and myself and others were ordered ashore posted to a mobile Squadron after being on the

there we found feverish operations in progress, to make up a convoy on the square - an impressive sight - were hundreds of vehicles, winches, 5 ton lorries, & hydrogen trailers, staff cars and the

Dispatch Riders motorcycles, we found we'd lots of work to do, loading blankets, balloon equipment, cooking utensils, paraffin, and stores, tents, even latrines buckets, & items too numerous to

mention. We were kept hard at it until midnight then we kipped down on the hanger floor. We grumbled then, little did we know what was to come.

In the morning we were detailed in crews, Jock luckily was still with me, and we had a decent Corporal, winch, wagon and trailer were allotted to each crew with all the accessories, the

organizing, (for the R.A.F. was good), and at I0 o'clock the Military Police opened the gate and the head of the convoy roared out to our unknown destination. The weather was cold and inclined to

rain so we as we left Essex we made the truck as comfortable as we could, packing the draft holes and making suitable seats - one good point - our vehicle was carrying the tea urn of hot tea for

our flight, and several times we helped ourselves, as we bumped along, it wasnít easy, I'm afraid we spilled as much as we drank. Midday found the novelty of the ride wearing off, we talked and

dozed intermittently, my pals in the truck were Jock, my old river pal, Mac, a Liverpool Irishman, Dickie Bownse & Spud Murphy, another exiled Irishman, we had now passed north of London and

making for the east coast, evening found us approaching Chelmsford, but as we could see balloons flying (mobile) there we knew that this wasnít our destination (little did I know they were

members of my old Runcorn Squadron). People stopped and stared as we travelled on and getting priority through the streets of Ipswich, convoys were no unusual sight in this part of the country,

but the winches, and hydrogen trailers had them guessing, reaching open country we made our first stop and opened our rations, the proverbial corn beef sandwiches, there was a hell of a row

about the quantity of tea, although we denied opening the urn the truck in front had seen the clouds of steam each time we removed the the lid, so we had to take evasive action. After a smoke

and a chat, all trying to prophecy our destination with

no enlightenment from our N.C.O's we piled in again and moved slowly away into

the gathering night.

was too dark to see much, the wheels of our truck splashed through mud a foot deep, it seemed to be an old cart track, eventually we saw the dark shape of airplane hangers and found we were

on an

airdrome under construction, we formed up in a long line on the main runway.

out, we roared with laughter, and Mac's language didnít mend things, We were detailed to carry our blankets and follow a Corporal, a member of the skeleton staff on the station, to our billets

these were widely dispersed, it was dark and we floundered on through the mud and water, I saw one chap slip and and in trying to regain his balance dropped his blankets in the lovely chocolate

mud, with a disgusted curse he just kicked them into a ditch and as far as I know left them there. Eventually I found a billet- the usual Nissen hut, but bare concrete floor, & no stove. Still after

another march to the cookhouse and a hot meal we crawled into bed

dead beat.

just as dawn was breaking, there was so much water

around that someone muttered It must be for 'bloody seaplanes'. I learned

later it's name was Thorpe Abbot and the Yanks took it.

convoy pulled

up on the outskirts of

nearby pub for beer and sandwiches. Then the Commanding Officer gathered us together in a field and gave us a lecture, this he said was our destination indefinitely and we were here because

the people had appealed for protection. Boulton Pauls works had been threatened and the employees refused to work with the lightning Hit Run Raids, we were also informed of Fifth column

activities, someone poaching the R/T system and giving 'Bed Down' instructions when we should be 'Flying'. We were given instructions to detach from the main column and move to the place

where we were to set up a site. I was shocked by the scene of desolation a small clearing in what had been a street of working class houses practically all demolished - it looked like an old photo of

Ypres - first world war, just heaps of rubble,

furniture still showing through the rubble - it was like a street of dead - no

one about - not even a stray dog.

inflate the balloon, and were now ordered to fly by six o'clock neat morning, why they always seemed to pick this unearthly hour I don't know. Late evening found the balloon fully inflated and

bedded down, the tent erected and our 'beds of sorts' fixed up in the 5 ton truck. the weather promised to be a little less bitter cold. we had only cold rations, but one of the boys was struggling

with a primus stove, so we managed a hot cup of the old 'char'. Immediately opposite the site we had noticed a small pub, a weather beaten sign denoted that it was the LORD NELSON, the

windows were boarded up so we presumed it closed, imagine or surprise when at seven o'clock a stout lady opened the door and called across to us a greeting, I remember I went across and when

she had finished asking me questions, I asked her if by any chance she sold beer ? Her answer was the best news I'd heard in days, immediately we all trooped across and lined up against the Bar.

She told us all the unhappy history of the raids, of house after house being demolished and her neighbours being forced to evacuate, that is the lucky ones, she said they all slept in the shelters

and hardly anyone came to the pub, and we could make it our homes in the evenings irrespective of whether we bought beer or not, This was our first instance of Norfolk hospitality, and the rest

of our stay left with me, at any rate a conviction that these were some of the finest people Iíd met. There was still lots of work to do on the morrow so we went early to bed, that is having worked

the guard rota out.

During the night the icy wind blew through the truck cover an it was just impossible to keep warm, although I had my greatcoat over my blankets. At 4.30 a.m. we were all up, luckily the chap

nominated as cook had managed to make tea. So we had a breakfast of cold corn beef standing around in the wet tent wrapped up like Eskimos. We were in touch with Headquarters by R/T thanks

to the hard work of the wireless bods, and on a given signal we released the balloon, at six o'clock it was just breaking dawn, around us rose the other balloons and we wondered what kind of

sites their keepers had.

I remember several civilians coming down the street on their way to work, and not one passed without speaking, they were obviously pleased to see us and the barrage. We heard after how

they had all been cheered on the way to work in the city, it seem it was the sole topic of conversation that morning, and the lunch hour found many who had sacrificed their dinner coming round

to the site, watching us work and trying to let us see how welcome we were.

And there was plenty work believe me, that night found us weary, Jock, Mac and myself had decided that the truck was no place to sleep so we looked for a hospitable abode in the street, it

wasnít easy, but at last we picked an empty shop, the windows of course were missing so we boarded them up, Mac cleared the rubble up from the floor, and although the ceiling looked like a

Christmas tree we decided it would do. Well we spread our straw filled palliasses on the floor and got down to it.

I think I slept about an hour, I awoke to find it was raining on my face and my blanketed looked as they had been white washed where all the wet plaster had fallen, Jock who was tossing

restlessly in a pool of water, lay behind a huge piece of plaster that threatened to crash on him any minute so I poked him. We got our feet to cheesed off to do any thing but blaspheme, I awoke

Mac but although he looked around him and realized the state he was in, said put my ground sheet over me, and turned over to sleep. Jock and I picked up our blankets and stumbled into the dark

street deciding to look for another billet. Someone shone a torch on us and it proved to be a policeman, he looked at us in amazement, I suppose we liked like two spectre's covered in white

plaster, using his torch he decided to help us, it seemed he knew a house which was fairly hospitable and he led us to it, it wasnít by any means cosy but at least the ceiling downstairs was, except

for one, pretty firm, so we

made our beds for the second time, after the chap on guard had made us some

tea which we shared with the friendly policeman.

and sleep in at night, our officer who seldom visited us didn't mind now we improvised, they were busy at it themselves. I remember how at night, we laid our palliasses out on the floor, eight of

us so packed that each palliasse touched and it was impossible to get up for guard without treading on somebody. Still it was fairly warm and dry, and apart from the mice and the smell we didnít

mind. Jerry paid us our first visit, as we were so near the coast the usual air raid warning was useless, so a crash warning was instituted this meant that he was over the city and if we werenít

already flying we had to move. That night he kept us company for two hours. As the days passed we got better organized it was now approaching Christmas, which wasnít a very bright prospect for

us but the pub which had now begun to thrive, thanks to Mac our pianist, and our noisy company, promised to be our haven, all the old neighbours and clients who had been forced to move to

other parts of the city made it a kind of ritual to come to their street and pub each weekend, it was pretty pathetic they couldnít do enough for us. They'd tell us each in turn of how their houses

had been lost, and sometimes their relatives. And I thought at times the songs we sung and the noise we made seemed like sacrilege, but they liked it, and we soon knew them all like old friends,

Old Bill the landlord, stern and proud of his last war years, Alf the butcher, Old Bill the humorist, the old cobbler and his wooden leg and Croix de Guerre, his wife who sang like an angel, and old

Ma the

landlady who always cried when we said goodnight, Real folk who had suffered

and could yet sympathise with others.

As I said they all slept underground and we soon realised it was wise. I remember how I felt standing in a flimsy tent on guard in the middle of a raid, it was impossible to leave the R/T set in

case instructions came through.

I've stood there thinking of a picture I'd seen at school of a roman sentry

standing at his post while

bombs kept missing although it got quite uncomfortable at times and I learned the value of a tin hat and good luck, I heard fire engines clanging their way trough the streets and I remember

Colman's factory getting flattened and Harmer's burning down.

Although by this time I really felt a Blitz veteran, Dark days it's all like a bad dream and this epistle is just touching on a theme. I'm proud to been there and shared with those people their

sorrows and dangers.

or a little coal, from these big hearted people, we were a happy crew. I recall how we would light the fire in the little kitchen after we had removed the bricks that had fallen down the chimney,

and in the evenings with the Hurricane lamp lit, our patched windows, and odd pictures covering holes in the wall, we'd sit and sing everything from Nelly Dean to there was an Old Monk, - Happy Days.

Still people were taking notice of the conditions under which we were living, and we heard that several had offered billets to us. But we spent Xmas 1943 in the old billet 'Dim View' we called it,

the old landlady loaned us a white cloth, and as a result of collections held in the pub we had a fine dinner with plenty of beer, cigs and mistletoe. The days passed, New Year I went home on

leave, the change was very restful, it was just like leaving the front line, and if the east coast wasnít the front line in those days I don't know what was, remember we had not invaded, our troops

were doing nothing, except

of course the anti-aircraft fire, and Jerry was concentrating all he had on our coastline

yet soon all that was forgotten. In

attacks and our chaps werenít having a pleasant time being out there in the open, without any protection. Later we moved into civilian billets, that is to sleep, and old couple leased us their

bedrooms, they of course slept in the shelter, three of us slept in each room,

the Corporal sleeping on the site and one man of course always being on guard.

you also had to listen for the R.T, buzzer, and ring Headquarters every 30 min's, to show you had not lost contact. If you were instructed to raise or lower the balloon during your tour of duty you

did it, alone. If this was impossible it meant waking the other fellows, in a gale of course it was imperative that every one was on the job. Many the time I've come off duty from say 12 midnight

until "2 o'clock, say I get to bed for 2.30, at 3 o'clock I've been ordered to rise again to "Storm Bed" the balloons against a gale. This would probably be completed in the blinding rain, by say 4

o'clock - back to bed, at six we would all have to leave our warm beds again as the sirens were blowing and it would need all of us to release the balloon. This done it was no use going back to bed

again as my turn for guard came again at 8 o'clock, (2 on 6 off), continually after that I would carry on my normal daily duties. This happened of course to all of us, and the strain could be seen in

our faces but we carried on.

pudding to their liking. About this time I was sent to the training site for a week prior to going on a board for my L.A.C. this made a change, but on my board I failed my winch driving, as the day in

question was blowing a gale, I appealed against the result, I knew I was a good winch driver, but no-one can drive a car up a hill in top gear if the opposition is to great, thatís what the board

literally asked me to do. Anyhow on my hearing I was granted another board, although I had to take all the subjects again. I passed - became a Leading Aircraftman and of course became entitled

to another 5 pence a day, which after

all, was all I was striving for.

Gale, Friday, Lose balloon , inflate.

Gale,

Sat, Rain and hail-sirens.

Gale,

Sun, Panel rips Deflate

-inflate. sirens.

Mon,

Busy wire splicing, raids- bombs -incendiaries.

Tues

, Air

(This

ends the period of time as a Balloon Operator)

retrieving 1000's of yards of cable draped over chimneys, churches and sometimes ships, all hard thankless work, fatigues, digging air raid shelters and trenches, pedalling the old bicycle though

wind and rain to fetch the rations, the dull monotony of standing for hours on guard through the dark hours, thinking over the past and trying to prophecy the future, if any. The heartbreaking

feeling when being awoke on a wild night by the guard standing in his dripping mac, sou'wwester and gumboots, saying "Your on next", when you seemed to have been in bed only a few minutes.

(Credit

AHT)