Click for Site Directory

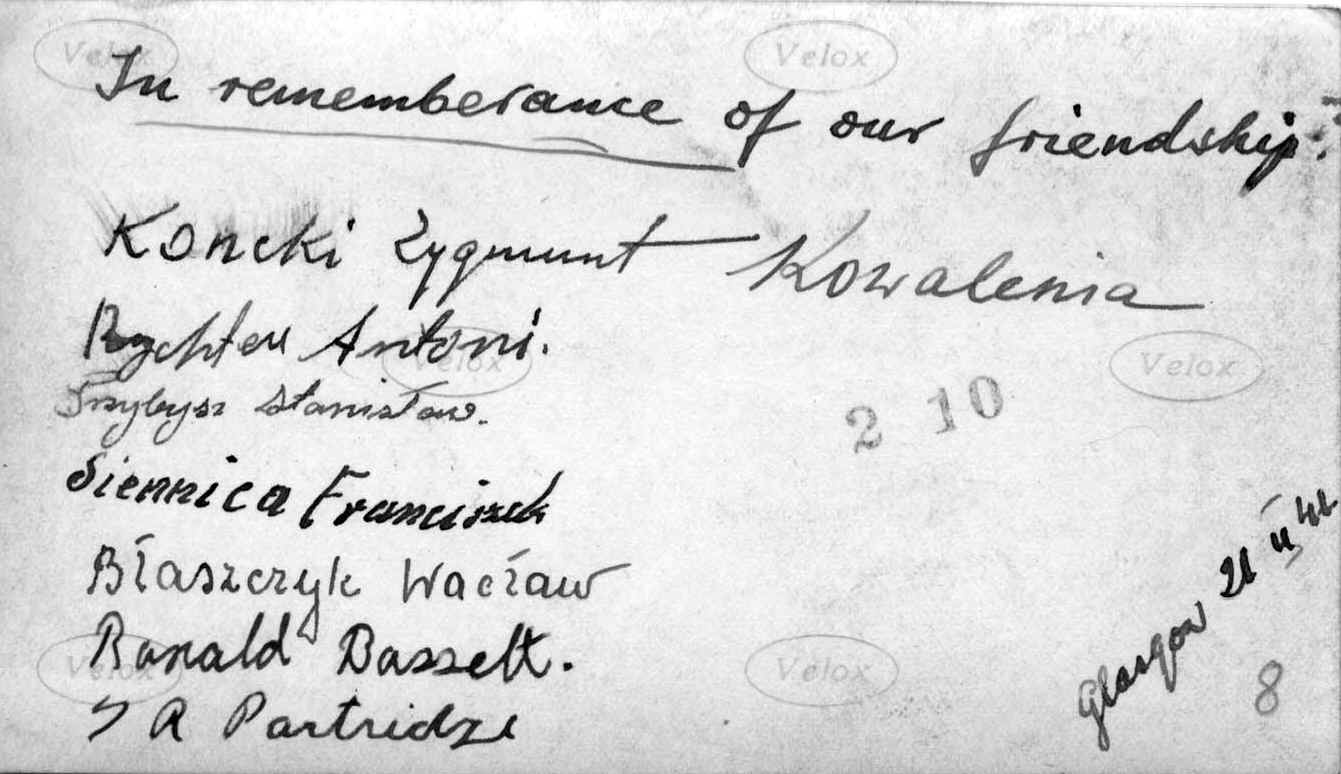

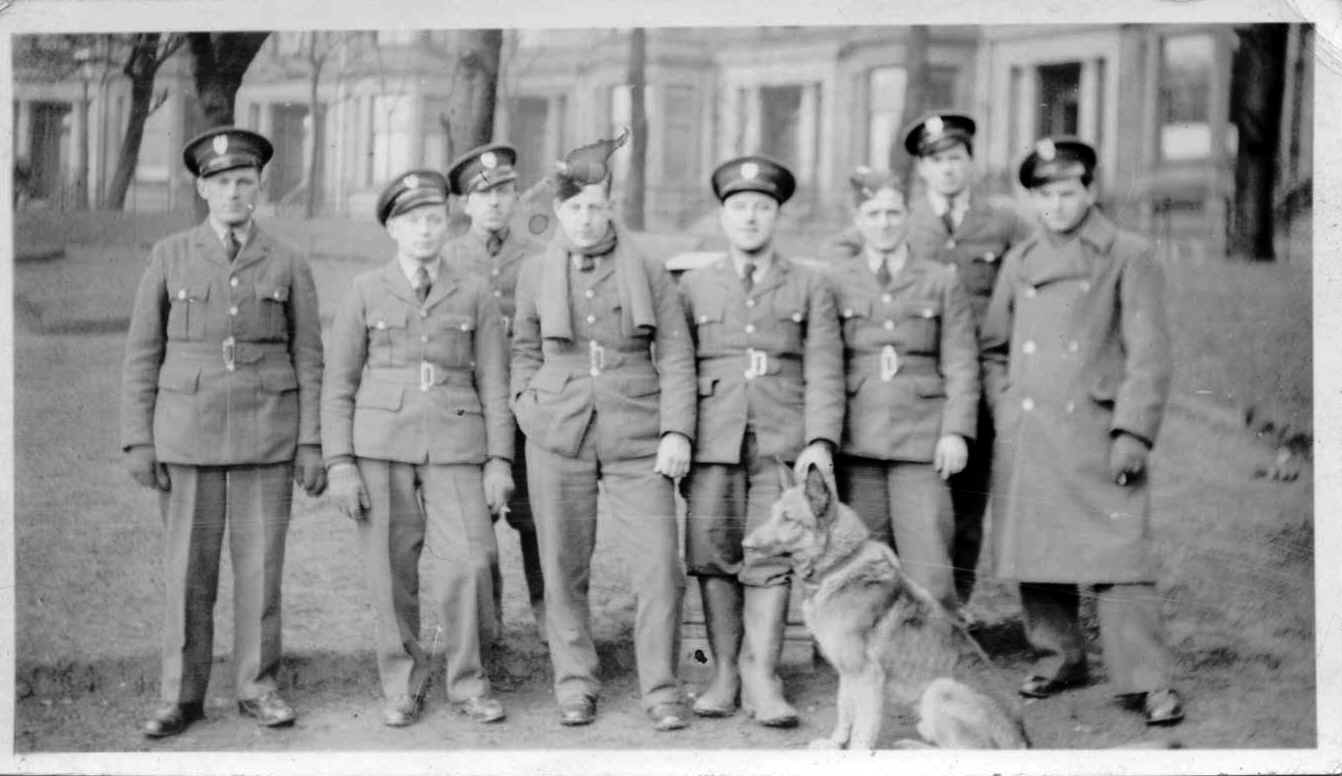

Click for Site Directory123713 Flying Officer Reginald Barrable

At the halt! Left form!

Memories of 123713 Flying Officer Reginald Frank Barrable during World War II

846779 Corporal LAC Reginald Frank Barrable 1908-1983.

He was given a commissioned and became 123713 Pilot Officer 28 July 1942.

Later he was appointed from Pilot Officer to 123713 Flying Officer 26th December 1942.

Retired retaining Rank 1st October 1954.

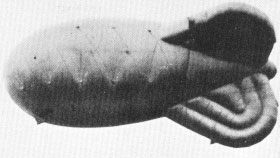

"As an Auxiliary Airman in Balloon Command, I eventually found myself a corporal in charge of a

waterborne balloon crew of five airmen, one of whom was always on a pass, so that we were always

a crew of four on board a barge anchored in the Thames Estuary. Ours was the M.V. Helen of Troy.

It so happened that the leave airman returned to the shore base at Sheerness (in peacetime the

Amusement Centre, in wartime H.Q. 952 Squadron).

With any luck, the returning airman would join a tug next morning for transfer to their respective

barges or drifters. Occasionally it would happen that one would have to spend a further day and night

ashore. When this happened, corporals often found themselves detailed as guard Commanders.

Now you must remember that we were Auxiliary Airmen with a little pre-war training concentrated

on Balloon Operating.

The ‘square-bashing’ part usually associated with enlistment in the armed forces was, in our case, almost nil.

We learned to march in step and swing our arms whilst doing so, and that the RAF salute, (mentioned to a few of us by a

‘regular’ LAC), was the longest way up and the shortest way down. To illustrate our lack of drill training I well remember the awful shambles when the

squadron was paraded and from two ranks we formed into fours (somehow) and marched the short distance from point ‘A’ to point ’B’.

All would have been well except that on arrival at point ‘B’ we were given the order to ‘halt’, followed by ‘left turn’, this order meant that what had

been the rear rank when we formed fours now became the front rank. This would not have mattered, but we were then given the further order to

‘reform two ranks’.

It had been quite an achievement to form fours, but to reform two ranks from a back to front position, well I’m sure those well trained in drill

movements in the days of ‘fours’ can imagine the chaos that ensued.

But to get back to the title of this article. Sure enough, the day arrived when I found myself back from leave, ashore, and as a corporal detailed for

Guard Commander duty. It wasn’t so much the Guard Room duties that worried me, but the preliminaries of parading the guard, (eight airmen) for the

Duty Officer’s inspection and then moving them to the Guard Room. I had never had occasion to handle a squad of airmen in any sort of drill formation.

In this respect I was not the only corporal so placed. Most of the waterborne corporals were in the same boat. (Forgive the pun.)

However, by dint of questioning shore-based corporals of more experience I got the ‘gen’ on the ‘preliminaries’. The drill was, to parade the guard in

two ranks of four with rifles at the slope, report to the Duty Officer (D.O.) that the guard was ready for inspection, Sir!

The D.O. having made his inspection would return to the ‘side lines’ as it were. The corporal in charge of the guard would then move the airmen to the

Guard Room. Simple enough? The snag was, the short marching distance from the inspection point to the Guard Room, and the number of commands

required from the Guard Commander to ensure that the guard finished up in front of the Guard Room and not somewhere outside the Main Gate and

across the road in front of Sheerness Railway Station.

I learned from the ‘experienced' that because of the short distance to be covered, once one started giving orders, it was essential to string all the orders

together without pause, otherwise the guard would surely finish up at the Railway Station. Consequently, after the D.O. inspection the Guard

Commander’s orders, without pause, went thus-

Guard by the left quick march eyes left eyes front at the halt left form halt.

I made it, just about. The guard were more or less facing the Guard Room. All I had to do now was post the sentries, change the sentries every two

hours, and stay awake all night.

Oh! One other thing; in the morning Guard Commanders were responsible for unloading the sentries rifles, as either some airmen couldn't count five

rounds or lacked experience of unloading as was evinced by the bullet holes in the corrugated roof of the Guard Room.

Of course, there was another occasion when there came the order in the stillness of the night “Turn out the Guard”, but that’s another story!

“REMINISCENCES OF A NOBODY IN RETIREMENT” Taken from the writings of Reginald Barrable.

1945

A repeat performance. Another war was over. Another road, another party. Gas lamps had given way to electric street lighting. Another set of people.

I recalled May 8th, my birthday and V.E. Day and I was unofficially on leave. Unofficially because I was returning to my Unit by a route that could hardly

be called direct (as required by the Service) although convenient in the circumstances, since it gave me a night at home. The war was practically over

anyway and the sooner I could get back to 'civvy street' and my wife and children and a regular routine, the better!

I had never regretted joining the Royal Auxiliary Air Force in October 1938. Two nights a week and one Sunday a month training to fly barrage balloons

and to drive lorries with trailers; to tie knots; to splice ropes; to 'walk' a balloon; to make a balloon-bed; to bed-down a balloon; to inflate a balloon.

Fourteen men to a balloon crew. In peacetime a 'regular' airman took two to three years to become a fully qualified Balloon Operator.

I was asked what trade I wanted to enter as. "A driver," I said. Came a Sunday when I reported for training when all drivers (there must have been forty

to fifty) were paraded and marched off to the M.T. sheds. "Step forward all drivers holding a licence to drive heavy vehicles," said the Sergeant.

Two men stepped forward. A whispered conversation between the Sergeant and the Warrant Officer. "Step forward all those holding a licence to drive."

The majority stepped forward and were told to move across and get into the cabs of the long line of vehicles which stood facing them.

I moved to the near-side door of one of the vehicles and was curtly told by a 'regular', a Leading Aircraft's man, "Round the other side, you're driving."

Somehow all the vehicles, Fordson Sussex 6-wheeler mobile balloon winches, got mobile and moved off in convoy. Miraculously, that Sunday morning

convoy got back to base without accident. Mind you, every time the convoy slowed, and it was necessary to change to a lower gear, there was a

lot of noise and the gearboxes must have suffered agonies. Once the art of double de-clutching had been re-learned, or just learned in many cases,

it was not so bad. When comparing experiences afterwards it transpired that the two men who had first stepped forward were 'bus drivers';

of the others there was a taxi-driver, and then came the drivers of light cars and one or two drivers of motorcycles and side-cars.

Balloon training, I found quite enjoyable and a welcome relaxation from the daily routine of my office job. I recalled my surprise on the first occasion

I hauled a balloon down on a gusty day in a built-up area. Everything was plain sailing until the balloon got below the height of the buildings when it

yawed from side to side and was in danger of striking the buildings on either side. Fortunately, a voice bawled, "Stop winch," and when the balloon

came back to an overhead position again, "Haul in winch," and another "Stop winch" when the balloon took another dive towards the buildings. It was

the 'regular' Leading Aircraft's man doing his stuff again. He, and several young men like him, was keen, energetic, and always ready to help the

'Auxiliaries', but yet must have resented their intrusion and rapid qualification as tradesmen, which on paper, made them their equals in a much

shorter time. They were on the same rates of pay and in the early stages of the war were deprived of their well-deserved promotion, since

they were teachers and instructors of the Auxiliary Airmen, a number of whom, when they were embodied for War Service, were promoted

to corporals in charge of balloon crews. Fortunately, these regular airmen were always around in the early days to put the Auxiliary

airmen on the right track. The 'Auxiliaries' could not have managed without them.

Embodied, on the 25th August 1939, for the duration of the war and flying barrage balloons in the London area all day, every day (& night) soon

proved as boring to me as the pre-war days of training and trade-tests had proved interesting. Sheer boredom caused me to volunteer for anything

that came along. The Orkneys was one posting I volunteered for, fortunately without success if one could believe the stories one afterwards heard

about the place. Chaps goings batchy with boredom, the cold, and the everlasting sound of the howling wind. Water-borne balloons were the

next thing for which I volunteered my services and this time I soon found myself on my way, destination unknown.

January 1940 - Destination unknown turned out to be Sheerness. A disused Naval Barracks on the outskirts that the Navy did not want even

in time of war. (I couldn't imagine that the Royal Air Force wanted it either, but beggars can't be choosers, and there was a war on).

However, from my kit-bag seat on a three-ton lorry, I listened to a Sergeant calling out names, the airmen jumping to the ground as their names were

called. My name, and several others, was not called. "You lot are billeted in the town." Said the Sergeant, and to the driver, "O.K. on your way."

There was an immediate babble of conversation and relief at the thought that at least we wouldn't be sleeping in 'that dump'.

With various home comforts no doubt, someone observed, "I wonder what the

land-ladies will be like?" "Hope we get some good home-cooking, I'm fed up with

living out of hay-boxes." There was general agreement with the latter part of

this remark, since we had all come from London balloon sites where each crew

were supplied with a large haybox, large vacuum flask, and a carrier cycle for

transport. Each crew member took it in turn to cycle to a central cookhouse

and collect the meal.

I recalled the early efforts and catastrophes of this meal-collecting. An

unladen carrier-cycle needs a bit of adjusting to, and to ride one laden on the

front with a heavy hay-box and out-size vacuum flask, the two containing food

and drink for fourteen men, was a bit of an art, to say the least. To one man,

whose turn it was, and who hoped to evade the duty by saying he couldn't ride

an ordinary cycle, let alone a carrier-cycle, the Corporal remarked, as he was given a push-off by willing helpers, "Well now's your bleed'n chance to

learn! Don't forget to keep pedalling."

To return to the billets in the town. The 3-tonner stopped at a row of

three-storey sub-basement terraced houses. No need to worry about what

the landladies and the food would be like. Both were non-existent.

Entering by the basement door our footsteps echoed and re-echoed as we

climbed to the ground and upper floors. No landlady, no carpet, no cosy

fireside chair, no fire even. In fact, nothing, or almost nothing. There

were electric light bulbs and blackout screens, and the floorboards were

our beds. There was a sergeant in the basement, the sea was just across

the road, and the weather was cold with every promise of being colder.

(Café - 'Donkey Serenade').

At some unearthly hour next morning the sergeant's voice roared up from

the basement (he didn't need to come up, he had what was known as a

good carrying voice) and in gumboots, great coats and scarves, with our 'small-kit' (towel, soap, razor, toothpaste, knife, fork, spoon, mug, plate) we

paraded outside our billet in the town!

The weather had more than kept its promise of being colder with a bonus of a good six inches of snow. There was no transport. The sergeant was

not one of those who rose fresh as a lark, and with a curt "Fall in, right turn, quick march," we were off to that unwanted, discarded, poverty-stricken,

naval barracks, Headquarters Royal Air Force, Sheerness, there to carry out our ablutions and partake of breakfast. The sergeant chose not to march

with us in the road but to walk on the pavement. The overnight snow was an undisturbed carpet of white, which made it difficult to see where

road stopped, and kerb started. The sergeant made the pavement but went base over apex in the process. The unexpected 'hands down' exercise

did him no harm, but he made good use of his lungs as he expressed himself in no uncertain terms about the weather. The airmen also made use

of their lungs with a good laugh.

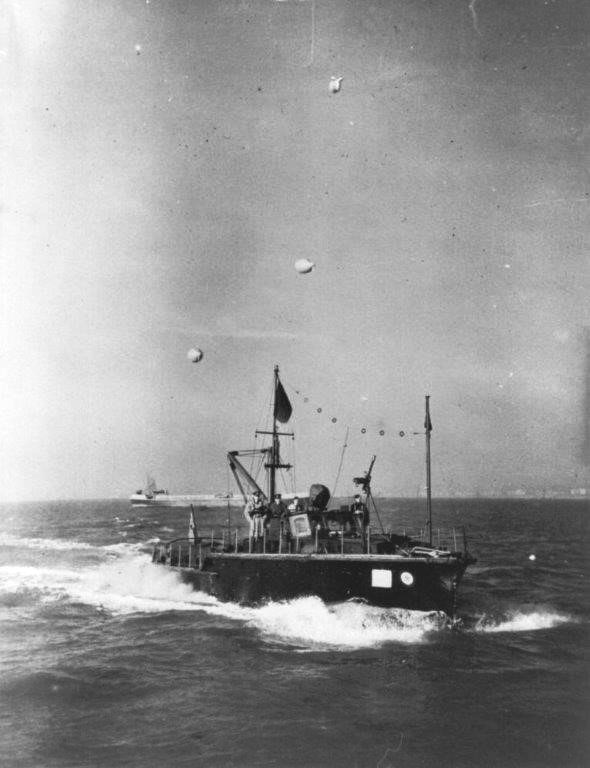

I smiled to myself as I recalled those days on water-borne balloons in the Thames Estuary. Those early days with the 'bastard' Squadron - no one had got

as far as giving it a number - with its motley collection of Lowestoft fishing drifters, Thames barges and assorted balloon winches.

Rough and ready accommodation beneath, in some cases, leaking deck timbers. I remember one vessel in particular with an assorted collection

of fifteen or so small tin cans to which the crew had fitted wire loop handles; at every leaky spot in the ceiling (the underside of the deck planking)

a screw hook was fixed; when it rained the cans were hooked up to collect the drips. They could not be left hooked up in readiness as there was

insufficient height and were apt to foul one's head.

Within a few days of arriving at Sheerness I found myself, one crisp,

bright, snowy morning on the end of the jetty in company with other

airmen, three of whom with myself formed one of the balloon crews,

waiting to board a vessel in the harbour. We were all strangers to each

other and a little apprehensive of what the near future held. As one of

them said, "Can't think why I volunteered for this job on the water. I

can't ride on a tram without feeling sick." His expectations of

seasickness were fulfilled when we eventually reached our anchorage in

the Thames Estuary,

about half a mile east of Southend Pier. The fact that the first meal on

board consisted of mutton (called lamb) stew, a greasy looking mixture

with a strong onion flavour, which moved from one side to the other

side of the soup plate with the rolling motion of the vessel. The vessel

was a motorised barge, some sixty feet long, anchored in the main

Estuary, the waves and the current pulling it one way and the balloon

up above doing it's best to break free. Well, it took a bit of getting

used to!

There were innumerable incidents flashing through my mind in those

months spent with 952 Squadron (Waterborne Balloons), some amusing,

and most of the trying times were amusing on reflection. One in

particular; a stormy night, pitch dark with torrential rain. The airman on

watch came below, leaving a trail of water as he moved, and awoke the

rest of the crew to report that he thought we had lost the balloon as he couldn't locate the cable from the leading-off pulley wheel going up to the

balloon.

Whilst the airmen on watch returned to the deck, the rest of the crew scrambled into their clothes and donned oilskins by which time the 'watch'

returned to say he had located the balloon cable, which instead of being in a more or less vertical position was running across the deck hatches

towards the stern of the vessel. This seemed to suggest that the balloon was down in the sea on the end of some 4,000 feet of cable.

The crew scrambled up the ladder into pitch darkness to be met on deck by cold driving rain and wind. We groped our way across the deck,

tracing the cable as we went, to find that it had hooked itself round hydrogen cylinders and other metal protrusions, finally taking a turn

round one of the lifeboat davits from whence it disappeared upwards to the stormy heavens. So the balloon was not lost, just flying from

an unusual mooring point - a lifeboat davit!

With the rain still coming down in torrents there was a suggestion that someone get

the croppers, bolt, airmen, for the use of, and cut the balloon adrift as it seemed

impossible to unhook the cable from the lifeboat davit in view of the tension on it.

Then it was remembered that we carried a cable clamp and block and tackle for just

such eventualities. This tackle was fetched, and someone managed, without falling

overboard, to get the clamp fitted to the cable at a point above the life boat davit and

then hook on one end of the block and tackle.

During this manoeuvre the possibility of the cable being struck by lightning was not

voiced but was very much on everyone's mind. It only remained to find somewhere on

the deck to fix the other end of the block and tackle and haul away until there was

sufficient slack cable to unhook it from the davit, when the balloon took up the slack

cable and things were back to normal, more or less.

It's a queer feeling, reaching with both hands above one's head, holding onto a rope,

with ice-cold rainwater running down one's arms and trickling across the chest and

then down to the tummy, waiting for someone to say "O.K., heave away." It contrasts

rather sharply with the uneventful pen pushing in an office and perhaps getting caught

in a shower at lunchtime, which had been my life prior to the outbreak of war.

There were, of course, the more war-like occasions; the magnetic mines, the acoustic mines, enemy planes making a run for it down the Thames at sea-level,

that fiery glow in the sky night after night which we knew was London 'taking it'. - a bright sunny morning when the ships in the Estuary were preparing to

move off in convoy and the vibrations from their engines set off the new mines, the acoustic ones.

The explosions, the ships at all angles. Several of our own vessels under-way for balloon inspection in Sheerness Harbour; of passing one of the 'drifters'

preparing to make the same trip. How we envied them their steam winch for hauling up their anchor. Ours had to be wound in on a manually operated

winch and hard work it was! We had passed the other vessel by some fifty to one hundred yards when there was a terrific explosion astern of us.

When we turned to look in the direction of the explosion we saw a terrific foaming, water spout fringed with debris, and when it had died down

there was nothing. It seemed likely that the vibrations from their steam powered winch had set off the mine over which they must have been sitting.

Maybe their engine and propeller would have had some effect had they got under way, but we no longer grumbled about our manually operated anchor winch.

The acoustic mine hampered balloon operations until the back room boys found the answer. The Squadron was in and out of harbour, operational,

non-operational, and then operational again, only to find one day that the waterborne balloons were the only vessels in the main channel of the Estuary.

The weather was fine and sunny, no winds and the sea flat and calm. This, and the absence of shipping, left a feeling of emptiness, like the City

of London on a Saturday afternoon in peacetime, I thought, as I went below to write a letter.

Our vessel was the M.V. 'Helen of Troy', of steel construction, and the crew were accommodated in the hold which was, of course, below the water

line. As well as the Royal Air Force crew of four, there was a civilian crew of three. On this pleasant sunny afternoon three of the airmen and two of

the civilian crew had left the vessel to row to Southend Pier, which was quite a hard pull and could be tricky according to tides and currents. They

were rowing because the mines had disorganised the ration tug and the crews were out of cigarettes and tobacco. An experiment with dried tea leaves

proved a stinking failure, hence the "pull for the pier." And so, the only two remaining on board were myself and the engineer, who was busy in the

engine-room. As I sat writing to my wife, I had been aware, in the unusual quiet of the summer afternoon, of a faint rapid metallic ticking noise

against the side of the barge, below the water line. I tried to ignore it, but now it was distinctly louder. As I put down my pen and pondered

on the possible cause the engineer came along the deck and poked his head into the hold and enquired whether I could "hear a ticking noise down

there". He could hear it in the engine-room. I joined him on deck, where the ticking was not apparent, and together we scanned the Estuary for a possible

reason. "I hope to Christ we're not sitting on a mine." said the engineer. I fervently hoped so too! And then, away in the distance we spotted the

only vessel that was moving, a tug, and as we watched it steaming steadily on it's way there was an almighty explosion and waterspout forward of the

tug, which appeared to let off steam and abruptly reduce it's speed.

That then, to our relief, was the answer to the metallic ticking on the side of the barge and the first success of the new acoustic minesweeper.

1946 - Demob. Return to the office.

I was demobbed in (?) August 1945 having served throughout the war, starting as an A.C.H in 'balloons'. And finishing as a Flying Officer in the Royal

Air Force Regiment. I never quite knew how I came to be commissioned into the RAF regiment. My name had been put forward for commissioned

rank in balloons I imagined, and I went before the GC. I heard no more from that interview and assumed the GC had turned down my application.

Some time later I was suddenly ordered to No.1 Balloon Centre at Kidbrooke to appear before a Selection Board. I thought this interview went quite

well. Anyway, I raised a smile or two from the Board. However, there was a complaint afterwards to units about the undiscipline of airmen appearing

before the Selection Board. Airmen going for interview in future were to be instructed to 'sit at attention'. I do recall resting my lower leg on my right

knee and clasping the shin with both hands. I find this a comfortable position when sitting on an ordinary upright chair and it kept my hands occupied.

Presumably I was one of the offenders, but I still don't know how one sits to attention. But I did get a new tunic out of it. When I arrived at No.1 Balloon

Centre the WO did not approve of my tunic. I would explain that some time after enlisting in October 1938 and before war broke out, we were issued

with uniforms etc. This was the usual set-up, starting at one end of the counter and finishing up at the other end with an armful of outer and under

garments, boots etc., and sign here. When I rejoined my friends I remarked "That's useful. Two pairs of trousers." And one of my friends said,

"You should have two tunics as well." Alas, I only had one. A storekeeper had pulled a fast one. I reported the deficiency to the Warrant Officer,

who was sympathetic, but try as I might, I never did get the other tunic, not until the Kidbrooke episode where I was issued with one, but spare

tapes were beyond them. An obliging WAAF in the stores very kindly removed the stripes from my old tunic and sewed them on the new one.

But I did not really win. It was an exchange and stores kept my old tunic.

And so, after pre-OCTV training at Filey (Butlins Holiday Camp it was to have been, but the RAF took it) but it was no holiday and once more

snow lay thick upon the ground and the only heating for the two occupants of each chalet was a hot water pipe running through each chalet

just below the ceiling. By standing on the bed and doing an arms upward stretch one could warm the hands, but this was hardly the most relaxed

of positions. Each chalet had one low wattage blue lamp which added to the feeling of coldness and gave one's fellow occupant a pallid look.

There was no blackout curtain for the door but there seemed to be an army of men on duty only too willing to demand one's name and number

for blackout offences. i.e., standing talking to a neighbour with the door half open. In fact, I've often wondered if that is where Larry Grayson

coined his expression "Shut that door!"

No, I can't say that I ever enjoyed Filey neither as airman or officer, winter nor summer. Mainly, I think, because whatever time of year I went

there I always felt cold. (I wonder how the holidaymakers find it?). Or maybe it was because it was my introduction to army life, for that

is what the RAF Regiment was, and the comparison between learning the trade of Balloon Operation and putting it into practice,

I found the infantry training of learning the rifle, the bren, the sten, the grenade, etc., and then having done all that starting again at the

beginning, rather boring to say the least.

Filey was followed by OCTV on the Isle of Man at Douglas for 3 months as an officer cadet. A hectic and rigorous three months! There was no

rationing on the island which was a consolation to be enjoyed occasionally after duty in one or other of the cafes.

We were accommodated in guest houses on the front at Douglas Bay and given a training timetable each week. This involved attending classes

at other places in the town for different subjects. Whoever drew up the timetable allowed no time for getting from A to B. One would be

doing P.T. from 8.30am to 9.45am on the sea front, followed by map reading at a hall somewhere in the town which was timed 9.45am

to 10.30am. Each instructor expected you to be there on the dot; impossible of course, but it meant a constant chase to try to achieve the

minimum lateness. A dash from P.T. back to the billet, up the stairs, out of P.T. kit and into battledress, grab the necessary map, notebook, etc.,

down the stairs and fall in outside and off to the lecture hall, there to met by the irate major in charge of training, watch in hand and demanding

to know why we were late. He was a Yorkshire man and it was useless trying to explain the deficiencies in the time-table timing.

There were odd occasions, rare ones, when we got one back at the major, as on the occasion of range practice firing with the bren gun.

The major was in one of his tiresome moods and nothing pleased him. His oft repeated order to one or other of the instructors of "Sergeant!

Tek 'is bleudy name. If 'e can't do it now, p'raps 'e can do it after five o'clock", made in respect of a cadet who had splayed the ground

with bullets midway between the firing point and the target.

The afternoon ended happily for us, however, when firing. We stood at ease behind the firing point and the major got down behind one of the bren

guns to demonstrate his capabilities with this weapon. Alas! His very first burst of firing splayed the ground between firing point and target;

immediately in a perfect mimicry of the major's Yorkshire dialect there was a shout from one of our number "Sergeant, take his bloody name".

There was laughter all round which made a happy ending to the afternoon.

Our three months training on the Island passed quickly - P.T. on the promenade first thing in the morning and then we seemed either to be scaling

Douglas Head or Onchan Head or at other times marching off inland between the two headlands, there to carry out some sort of military exercise

usually involving a lot of physical effort (seemingly to no great purpose). I suppose we did learn something, even if it was only how to suffer

in silence. These exercises usually finished with a discussion on the merits and de-merits of what we had done when the officer in charge

would suddenly look at his watch and announce "Sorry chaps, but its later than I thought. We shall have to force march back". This involved

spells of moving at the double and for the last two hundred yards there would be the cry of "Gas!". Not the most comfortable of headgear

at any time, certainly not for running, are gas masks.

Sometimes on these exercises we would march out to our rendezvous point, there to be met by the major, who would assemble us around

him whilst he briefed us on the nature of the morning exercise. He would conclude "Now what time is it?" Whereupon some eager cadet

would oblige him by announcing the time. "It bloody isn't y'know." We soon learned that only the major's watch showed the correct time.

All articles and images -Courtesy of the generous family of Reginald Barrable