Click for Site Directory

Click for Site Directory

Collisions With Balloon Cables and "Squeakers"

It was every pilots' nightmare, irrespective of being a friend or foe, colliding with a balloon cable generally meant damage to the aircraft with a loss of control or damage that caused a stall

from which the plane could not recover. Every balloon flying was a threat to friendly aircraft as much as enemy ones. In order to minimise the risk to friendly aircraft, the crews were given the

positions of balloon barrages and ordered to fly around them and avoid the general area.

In fact, flying in a balloon barrage area was prohibited without permission, when balloons were close-hauled to minimise risk. The only exception to this was given to our fighters when

pursuing German aircraft. Even so the diaries of Balloon Command are littered with hundreds of sightings of friendly aircraft blissfully flying over barrages and through barrages much to the

consternation of the balloon crews and officers.

Within 5 days of war being declared and barrages being operational, a Swordfish aircraft was flying over Plymouth at 2,500 feet through a barrage that was at 5,000 feet. It hit a cable.

Despite wing damage, the pilot managed to recover from the dive at around 2,000 feet. His wings were cut by the cable but not enough to give a total loss of lift.

By 20th June 1940, when Balloon Command had scored two victories over the enemy, (one at Le Havre on 4th June 1940, causing a Junkers 87 to crash and one at Billingham on 20th June

1940 causing a Heinkel to crash into the sea) eleven friendly aircraft had hit cables with 5 of these being fatalities.

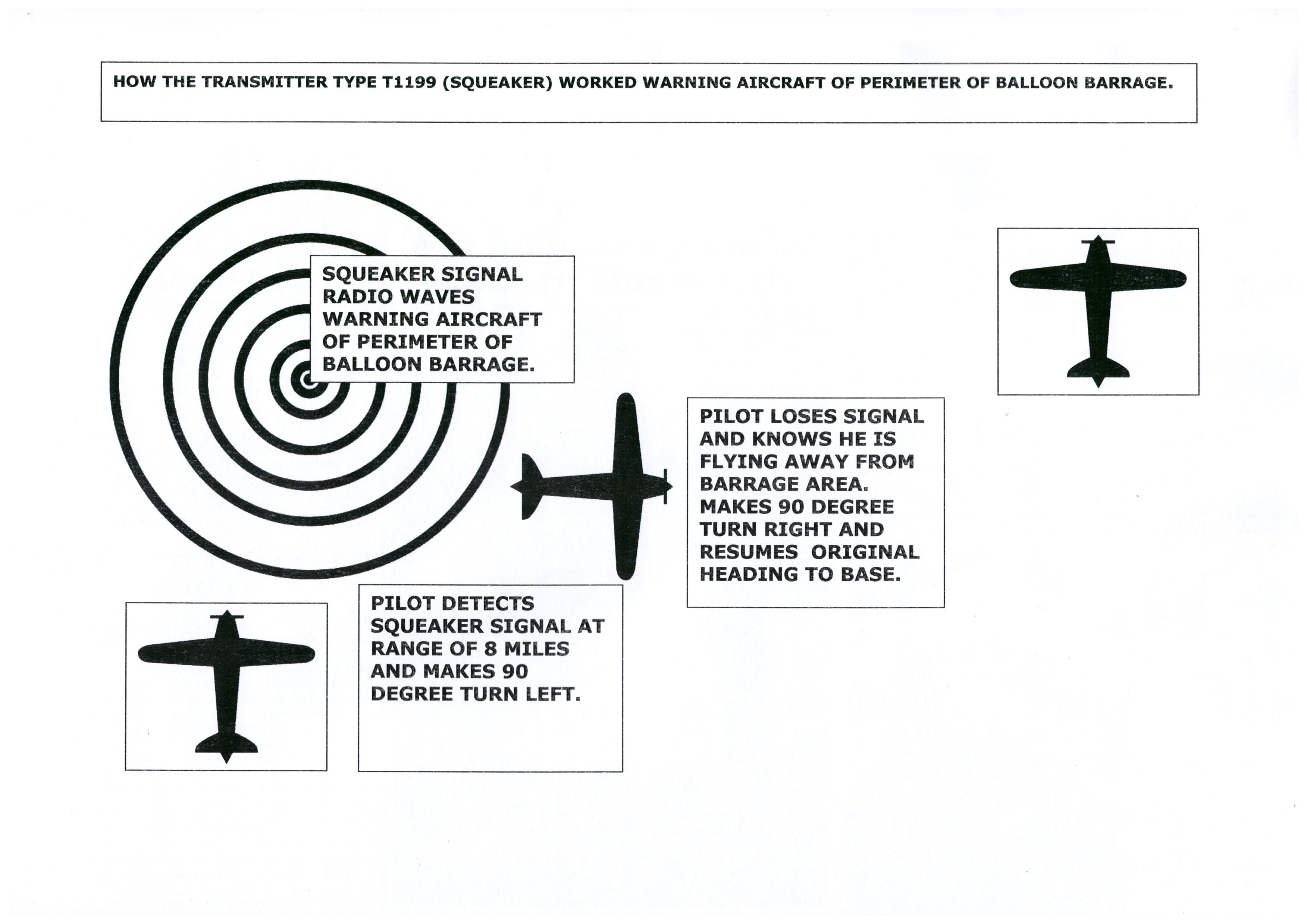

In June 1940 Captain D.H. de Burgh of the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough was tasked with a method of making aircraft aware that they were in the proximity of balloons.

Suggestions varied from various coloured searchlight beams, ground mobile radio beacons, lights attached to the balloon cables, and other radio methods.

On 11th July 1940 he had devised a small transmitter putting a signal into a 25-foot aerial. The frequency was from 6.5 mc/s to 6.10 mc/s this was to meet the frequency on which most

operational bombers were using on their TR9 receivers in the aircraft. The TR9F set was under the seat in most bombers.

Later that month an experimental set-up was made at Harwich and a Wellington bomber was used in trails of 1500 feet to 4,000 feet with satisfactory results. The transmitter provided a definite

an abrupt note as soon as the aircraft came within 8 miles of the transmission.

They made a further 3 units with minor modifications and these found their way to Dover, Thames Estuary, Harwich, Hull and Billingham. It was decided to place them in all barrages in

such a way that they gave a signal to warn aircraft when 8 miles for the balloon perimeter.

A request was made for the RAE to make 100 sets. It was found that due to the size of some barrages one central set could not cover every barrage and in some cases, it was agreed to have not

just one central set but several to be placed on the barrage perimeter.

It was decided not to place them on ships as the signal could assist the enemy in detecting the convoy location. The sets were required to work continuously at night and in conditions of low

visibility. It was decided that there should be around 300 Squeakers which would allow sufficient reserves for replacements. The large barrages such as London and Glasgow had as many as eight

Squeakers to give enough coverage.

The information about the Squeakers was circulated to all in Balloon Command on 15th October 1940. In November they were being made at the rate of around 20 per week. There were

eventually 3 types one with a red band operating on 6.41 mc/s to 6.47 mc/s for Bomber Command and a yellow banded one operating on 6.425 mc/s to 6.45 mc/s for Bomber Command restricted

frequency. The last type was also a yellow band operating on 2.405 mc/s to 2.42 mc/s for Coastal Command.

Electronic equipment in 1940 was not well protected and as the numbers were increased the failures of these Squeakers began to increase.

The initial approach was that the barrages east of a line from London to the Thames estuary and on a line Lincoln, to York to Newcastle, would be close hauled on those nights when our

bombers were returning from missions. This covered barrages from Harwich, Humber, Tyne, Tees and Blyth. The timings for close-hauling were decided between the various Commands involved.

This included those waterborne balloons who were hauled down to 1,000 feet during blackout hours. Bomber Command agreed to inform Balloon Command 15 minutes after sunset of the balloon

barrages to be close-hauled. One idea was to fire rockets every two minutes in the East coast barrages when it was known that our aircraft were returning. This was never proceeded with due to

communication difficulties.

Of course, quite typically this dialogue between Bomber Command and Balloon Command did not sit well with the people in charge of Fighter Command. Their view was that to close-haul

balloons when enemy aircraft were constantly operating in these areas was "undesirable" because it made the balloon barrages non-effective as a measure of defence. In addition, on waterborne

sites conditions might prevent the close-hauling to 1,000 feet.

Fighter Command suggested in July 1940 that a number of mobile flashing beacons might be used and rather bluntly suggested that Bomber and Balloon Command consider this option. These

became what was known as Balloon Marker Lights.

This option caused much consternation for various civil authorities and private individuals who thought that was simply advertising their position to the enemy.

The other idea was to have a radio device on an aircraft that would detect a radio signal emitted from a transmitter attached to a 25 foot aerial. This would emit a sound like that of an air

raid siren and was designed to be detected by the inter-communication system in our aircraft when at a range of 8 miles away. Experimentation of a radio device that would emit such a signal was

begun at Harwich.

While experimentation with a radio device took place it was decided to fix red neon lights even as a temporary measure to balloons on coastal barrages at Tees, Hull, Forth, Tyne, (including

Blyth), Harwich, Thames Estuary, Portsmouth, Southampton, Bristol and Liverpool. As a result, marker lights that could be seen from 50 miles away, at points 5 miles to the north and 5 miles to

the southern boundaries of a balloon barrage were implemented. The idea was to have a steady red neon light for the northern boundary and a flashing red neon light for the southern boundary

ones. The frequency of the flash was once every 25 seconds.

The balloon crews were expected to provide all the servicing, maintenance and repair that went with these lights. This required a team of one Corporal (ACH), one aircraftman (electrician)

and one aircraftman (Fitter MT). The marker lights that flashed were operated by a mechanical cam and these cams proved to be problematic, resulting in a redesign so that the cam activated a

flash for 5 seconds duration or 12 times a minute. They were switched on between dusk and dawn as well as in conditions of poor visibility.

As one can imagine there had been no consideration to have duplicate Marker Lights at these installations so that in the event of one failing a substitute could be brought into action quite

easily. Once a Marker Light failed it was essential that friendly aircraft were informed, and Balloon Command would send an immediate signal to all Home Commands to inform them that the

Marker Light was out of action. This communication route was far to slow and so it was decided to inform Air Ministry who had to take on responsibility for the dissemination of this vital

information. During their lifetime the Marker Lights were constantly re-sited for many reasons.

However, the radio devices also proved of value and mass manufacture began and in time all barrages were equipped with these radio devices that became known as "Squeakers". For a time

both warning devices were in regular use.

Despite these technologies in the summer of 1940, twenty friendly bombers hit our balloon cables with a loss of ten crews. These had all occurred in good weather and consideration was given to

the risk that winter weather would cause higher toll.

As a result, a decision was made by the Air Ministry that allowed Fighter Command, at the discretion of the Commander in Chief, to be able to order close-hauling of barrages if such a request

was made by Bomber Command. This information was not given to Bomber crews who were expected to continue to fly and take the usual precautions against hitting balloon barrages. Balloon

Marker Lights were required to continue to operate.

This new policy was implemented with specific rules for each of the city, country and estuary barrages.

Even so, the worst fears of Bomber Command were realised through the winter of 1940-1941. Between September 1st, 1940 and 2nd February 1941 there were 43 cable collisions by

friendly aircraft and 9 cable collisions by enemy aircraft. This one-sided ratio is somewhat explainable by taking into account that the density of aircraft over the British skies, at any one time,

throughout the war was much higher for British aircraft. Also, during that time many Balloon Squadrons had noted friendly aircraft flying through their barrages but getting through unscathed by

luck rather than any judgement. The Crewe barrage recorded nine friendly aircraft flying through or over their barrage in one month!

This was due to:

Since most losses were linked to daytime flying it was decided that Balloon Command had and were taking every possible activity, short of being non-operational, to maintain the safety of

aircraft and pilots. The remedy lay with Bomber Command and Fighter Command to ensure pilots were briefed properly and threatened with disciplinary action if found guilty of flying in barrage

areas.

From January 1941 it was decided to switch Marker Lights off in areas that were under attack or where attacks were a clear threat.

The Air Ministry ensured that pilots were provided with an information room with maps showing the areas covered by balloon barrages were on display. In addition, pilots initial training was

to develop techniques to memorise the areas covered by balloon barrages. Finally, pilots were made to realise the consequences of striking a balloon cable, in terms of the lives of their crew and

the civilians below. Despite this there seemed to be no change to the casualty rate.

In May 1941, a total of 28 friendly aircraft had struck cables and 98 friendly aircraft had flow through or over barrages but had got through unscathed. Most of these were daylight flights. The

Air Ministry decided that pilot ignorance was now no longer an excuse for these infringements.

In June 1941 Balloon Marker Lights were totally withdrawn, much to the relief of civilians living near to one and replaced by Squeakers.

Paradoxically the replacement of Marker Lights by Squeakers was as unpopular with air crews as the Marker Lights had been with civilians!

Crews claimed that the Squeaker signal swamped the inter-communications system on an aircraft when near a barrage area, making on board communication impossible. One interesting

finding was that when investigating a balloon cable collision by a friendly aircraft the crew nearly always insisted that the no Squeakers had been heard even though the log showed they were

operational and had no serviceable issues at the time.

In May 1941 a conference had been held on the issue of balloon cable collisions and it was revealed that only 7 friendly bombers passed over the Humber barrage in March 1941 and that on

withdrawal of the Marker Lights and substitution of Marker Lights at this barrage in April 1941 the number of infringements was now 57 friendly aircraft. The Conference recommended a return to

Marker Lights. This did not please Balloon Command.

They defended Squeakers vigorously, No. 44 Squadron, 5 Group had complained that Squeakers were very effective but were far too frequent and prevented inter-communication between

the crew.

To add insult to injury Coastal Command also waded in with a complaint that Squeakers were interfering with ordinary radio traffic and wanted Squeakers removed. It was a typical case of

pleasing some of the people some of the time but not all of the people all of the time!

While the Air Ministry were digesting this attack on Squeakers and presumably reconsidering Marker Lights a German Bomber was shot down in June 1941 and a enemy document was

recovered showing the exact location of the British Marker Lights. This sounded the death knell for these lights.

Air Marshall Sir Sholto Douglas of Fighter Command advised that in view of the huge increase in infringements in May 1941, consideration should be given to disciplinary action in more

flagrant cases.

In June 1941 there were 72 infringements by friendly aircraft, the highest number ever, the majority having occurred in good daylight. It was then decided to bring all perimeter balloons

down to below cloud base provided it was not less than 1500 feet. This it was hoped would enable the perimeter balloons to act as markers for the Allied pilots. It was put into practice and in July

1941 there were 72 infringements by friendly aircraft. In addition, pilots were instructed in balloon defence and the implications for them if they hit a cable. In August 1941 there were 42

infringements by friendly aircraft but in September and October it was 50 and 63 respectively.

Air Marshal Sir Leslie Gossage suggested that one option was to ground the barrage except when warning of an attack. This was at odds with the policy of keeping the balloons up at all times.

It was decided not to aircrew aware of this policy as it was thought the crews might act recklessly if they knew.

After much discussion between all three Commands, it was decided to ground all inland balloons but keep the coastal ones flying. The inland ones would be let up if an attack was imminent.

The sight of a balloon aloft was a reassuring sight for civilians, it kept them comforted and reassured that the skies were being defended. In order to maintain morale, it was agreed to fly balloons

to operational height at least twice weekly to maintain crew skills and to maintain public morale. Trials showed all this was possible with crews being able to get a balloon up in time when an

attack was imminent provided they had sufficient telephone warning.

The policy worked as although infringements actually increased, collisions fell.

In August 1942 the number of infringements was 245 which resulted in nine collisions, two of which had fatal results. It was clear that the policy of close hauling had leaked out and crews

were being reckless because they felt they could get away with it. In December 1942 there were 368 infringements, this confirmed the view of Balloon Command that pilots were now very aware

of the close-hauled situation and taking reckless advantage of it.

During the war there were 54 collisions between enemy aircraft and cables of balloons, 25 of these produced "kills" and 22 escaped while for the remaining 7 aircraft no information was to

be found.

© Peter Garwood 2016