Click for Site Directory

Click for Site Directory

BEWARE!

Balloons over Birmingham

RAF Balloon Command was an integral part of

Britain’s air defence, but these silvery beasts were hard to control and would

bite friend and foe alike.

By Steve Richards

Towards

the end of 1940, Birmingham was in the thick of the Blitz. Things were, however,

relatively quiet on the night of 8th November, with just two German

bombers belonging to a crack Luftwaffe unit dropping bombs on the city. There

was though, a third aircraft droning overhead. This was a lumbering RAF Avro

Anson. On board was the normal four-man crew, plus a specialist wireless expert.

The aircraft belonged to the Wireless

Intelligence Development Unit based at Wyton, Huntingdonshire (this RAF airfield continues to specialise in

electronic intelligence gathering). On this particular winter’s night, their task was

to gather information on German radio beam transmissions then being used by the

Luftwaffe to guide bomber aircraft to their targets. The dedicated fifth man in

the Anson would have been especially eager to pick up signals being used by the

two Heinkel He 111s that had been operating over the city because they came from

the unit KGr100, which was using a sophisticated radio beam system known as X-Verfahren.

Shortly

after midnight, while flying over the Stechford area of the city, the Anson’s

airframe shook violently and turmoil ensued inside the cabin. The machine was

plunging earthwards. Within the cramped, dark fuselage there was little hope of

any of the men grabbing a parachute and managing to locate the rear door or,

indeed, any emergency exit. The aircraft had struck a barrage balloon cable. It

crashed onto the LMS railway track. All of the crew were killed.

The Anson was not unique in falling foul of the balloons suspended over Birmingham and its outskirts. In fact, during the war, a dozen friendly aircraft came to grief because of these balloons, resulting in many allied personnel dying.

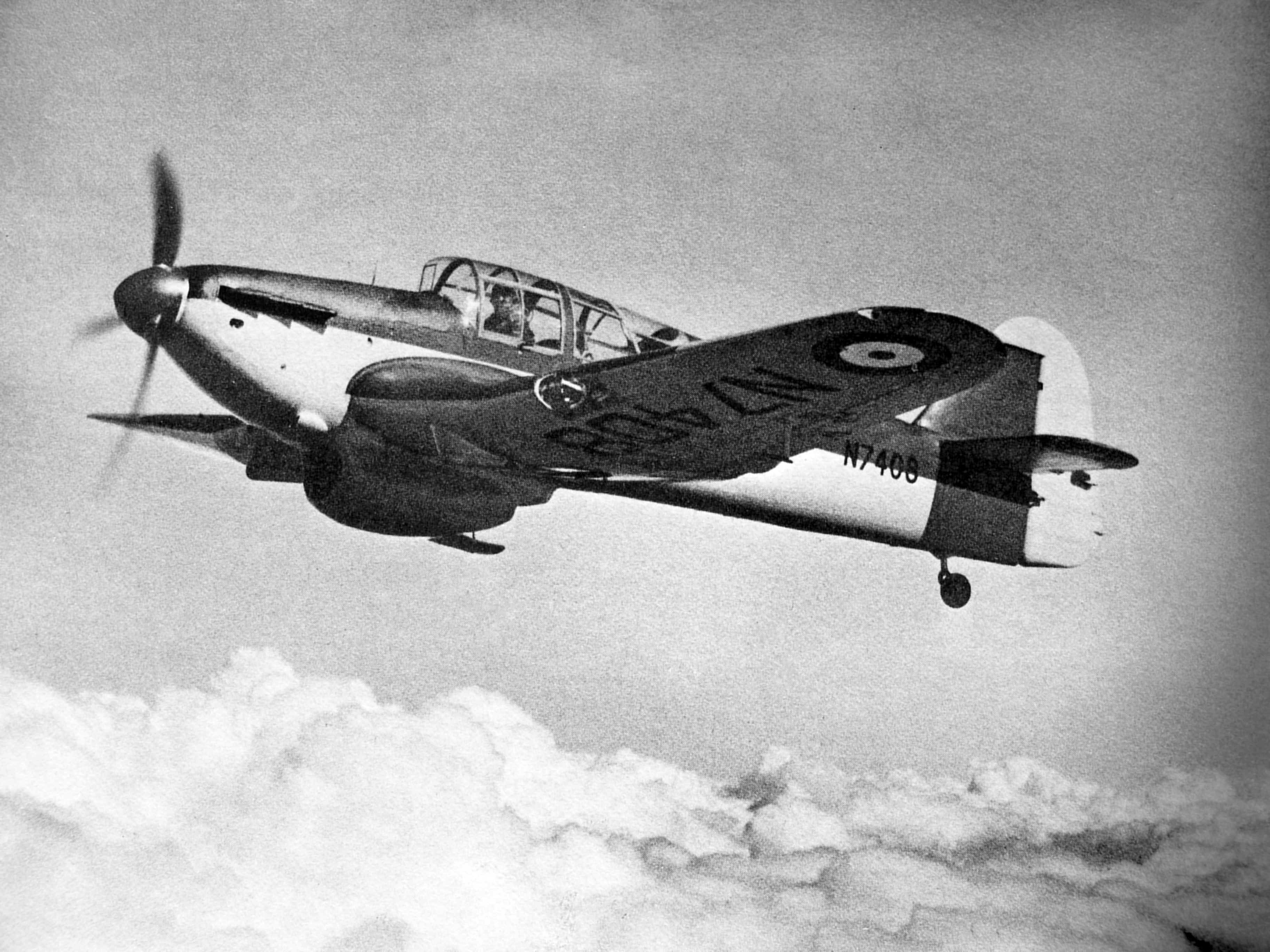

Shortly after midnight, (therefore on 9th November 1940) an

Avro Anson, like the one illustrated, crashed onto the LMS railway at Stechford

having struck a balloon cable. Authors

Collection

The elephantine

barrage balloons were suspended in the skies over many British towns and cities

from September 1939 until late in the war. They were looked upon with some

affection by the civilian population and the crews who operated them, even to

the point where ‘their’ local balloon was christened with names such as

Barry the Barrage Balloon, or Matilda, Annie, Susie and Romeo.

The

balloon and its operation

The streamlined

balloons were large, 63 feet long and 31 feet high, and made of specially

treated, rubber-proofed cotton fabric. The gas bag had a capacity of 19,150 cu

ft and weighed 550 pounds. The balloon was flown on a flexible steel cable of

0.31 inch diameter and it was this cable, rather than the balloon itself, that

deterred aircraft from flying in the vicinity of balloons. A collision with the

cable almost invariably meant that the aircraft would not make it back to base.

As barrage balloons were inflated with hydrogen gas, which is much

lighter than air, the balloons were able to rise thousands of feet skywards,

tethered by their lethal cables. As the balloon gained altitude, the atmospheric

pressure diminished and, as a result, the hydrogen gas expanded. For this reason

the balloon was designed to make allowances for the expansion of the gas. A

false bottom permitted the lower cavity to be filled with air which, as the

hydrogen gas expanded, was expelled. This false bottom was called the ballonet

and the flexible wall which separated it from the upper (gas) chamber was

referred to as the diaphragm.

When the balloon was

inflated the upper compartment was not filled to capacity with the hydrogen gas.

The ballonet was filled with air through its wind scoop. As the balloon

ascended, the atmospheric pressure dropped, the hydrogen gas expanded pushing

down on the diaphragm and so expelled the air. When the balloon descended, the

ballonet scooped in air as the gas contracted, so that the shape of the balloon

remained constant. Three air-inflated stabilisers ensured that the balloon flew

at an even keel always head towards the wind.

Maintaining and

flying a barrage balloon was heavy and demanding work. Normally a balloon site

was manned by two corporals and eight men. From 1941, personnel from the

Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) were also actively employed in operating

the balloons. At first, the women were formed into mixed crews with the men.

Later, exclusively WAAF crews were used; these numbered 16 to a crew because of

the nature of the heavy workload.

When in flight,

balloons were vulnerable to lightning strikes, as the steel cable acted as a

conductor. The hydrogen gas with which the balloon was filled was particularly

inflammable; a lightning strike generally meant it was impressively destroyed by

fire. During autumn 1939, lightning strikes on balloons in the London area saw a

massive 80 balloons destroyed in a single afternoon. Snow and ice were also a

problem, making the balloon heavy. Wind was the biggest challenge, especially

when trying to bed the balloon down. As the war progressed, new equipment and

techniques ensured a more efficient operation. Gusty conditions could cause a

balloon to break loose from its mooring site and float off trailing its steel

cable which wrought havoc upon chimneypots, roof tiles, tram wires, lamp

standards etc! Balloons were also vulnerable to attacks by enemy aircraft

and shrapnel damage from exploding anti-aircraft shells.

Heinkel down

Soon after midnight

on 10th April 1941, a German Heinkel He 111P was critically damaged by an RAF

nightfighter of 151 Sqn. As it lost height over the suburb of Quinton, it struck

a balloon. The bomber crashed onto houses in nearby Warley, killing all seven

occupants. The incident was, however, a morale boost for the 915 Squadron

balloon crew. The reality is that the aircraft was doomed already. Each member

of the barrage balloon crew was issued with a commemorative medallion made from

metal taken from the wrecked Heinkel.

Although some German aircraft fell victim to balloons, the

primary purpose of the balloons was to discourage low flying by the enemy. The

passive role of the balloons meant that the operating crews had little to

encourage them, despite much hard work.

RAF Balloon

Command

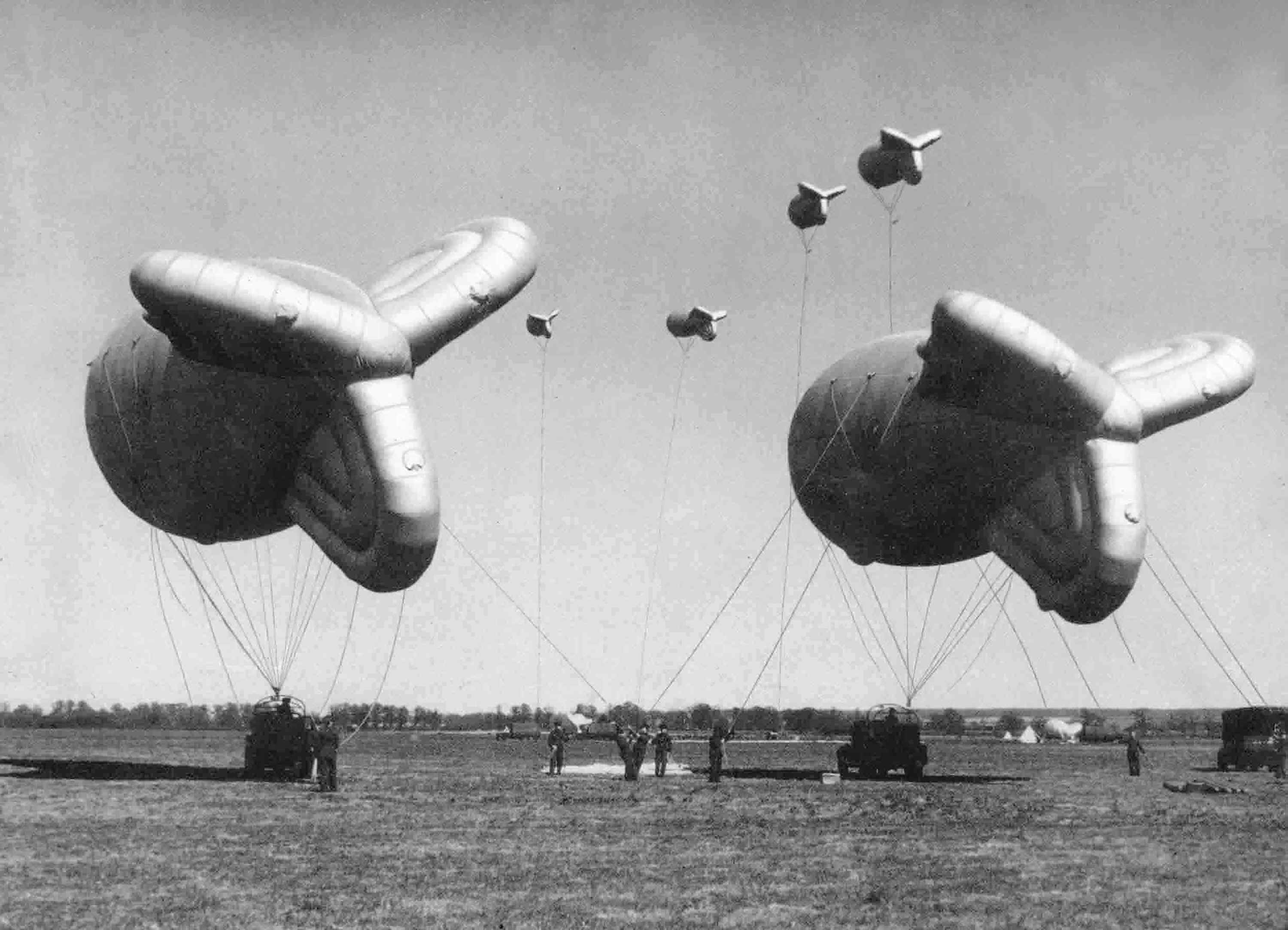

This photograph was

obviously taken at a balloon station, rather than a site, possibly RAF

Cardington. Courtesy of Peter Elliott (RAFM)

Whilst

anti-aircraft guns and searchlights were the responsibility of the Army, barrage

balloons were a part of the Royal Air Force. Following the establishment of a balloon barrage

over London during 1936-1938, the Air Staff became convinced of the value of

such barrages as a means of keeping enemy aircraft at reasonably high altitudes.

It was therefore decided that key provincial towns and cities would have their

own barrages and so was born RAF Balloon Command.

Balloon Command was

divided into five groups (numbered)30-34)and

these were subdivided into Balloon Centres. These centres governed the squadrons in the field,

providing supply, maintenance and administration (including sick quarters). In

the beginning units were established on a skeleton basis with a small force of

regular personnel which was supplemented by local part-time auxiliaries.

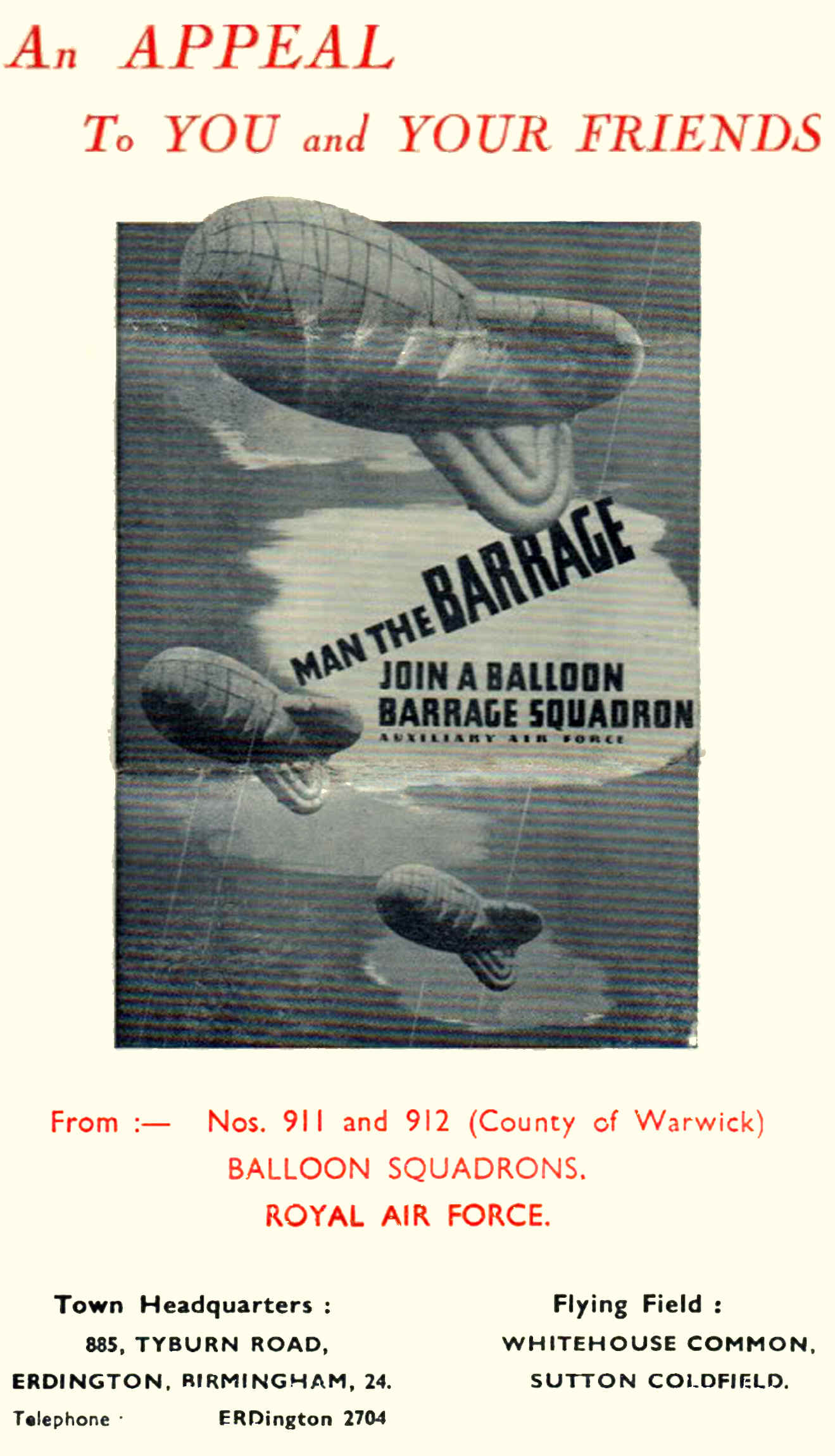

A

local recruitment poster encouraging applicants to join 911 and 912 Squadrons,

part of 5 Balloon Centre, Sutton Coldfield. Reference to 912 Squadron is

interesting; this unit was transferred to Gloucestershire soon after the Dunkirk

evacuation.

Recruiting for the Auxiliary Air Force barrage balloon squadrons began in

the first weeks of 1939. Typically, the Territorial Association (TA) volunteers

were aged between 25 and 50. They trained during the evenings and at weekends

throughout the summer months, receiving instruction from regular serving RAF

instructors.

Mobilisation took place in August 1939 and in April 1940, a number of

balloon squadrons were obliged to provide mobile units for service with the

British forces in France. These units were sent to RAF Cardington, Bedfordshire,

and were then dispatched to their port of embarkation. Just weeks later their

equipment was abandoned in the face of the German onslaught but personnel were

evacuated safely in late May. After disembarkation leave, they re-mustered

at RAF Cardington for training and re-equipment.

By the summer of 1940, with the exception of London, Birmingham had more

barrage balloons than any other defended area in the country. This was a total

of 168 balloons and they were flown by four squadrons viz 911, 913, 914

and 915. The first two of these came under 5 Balloon Centre at RAF Sutton

Coldfield and the last two under 6 Balloon Centre at RAF Wythall. All were a

part of 31 Barrage Balloon (BB) Group.

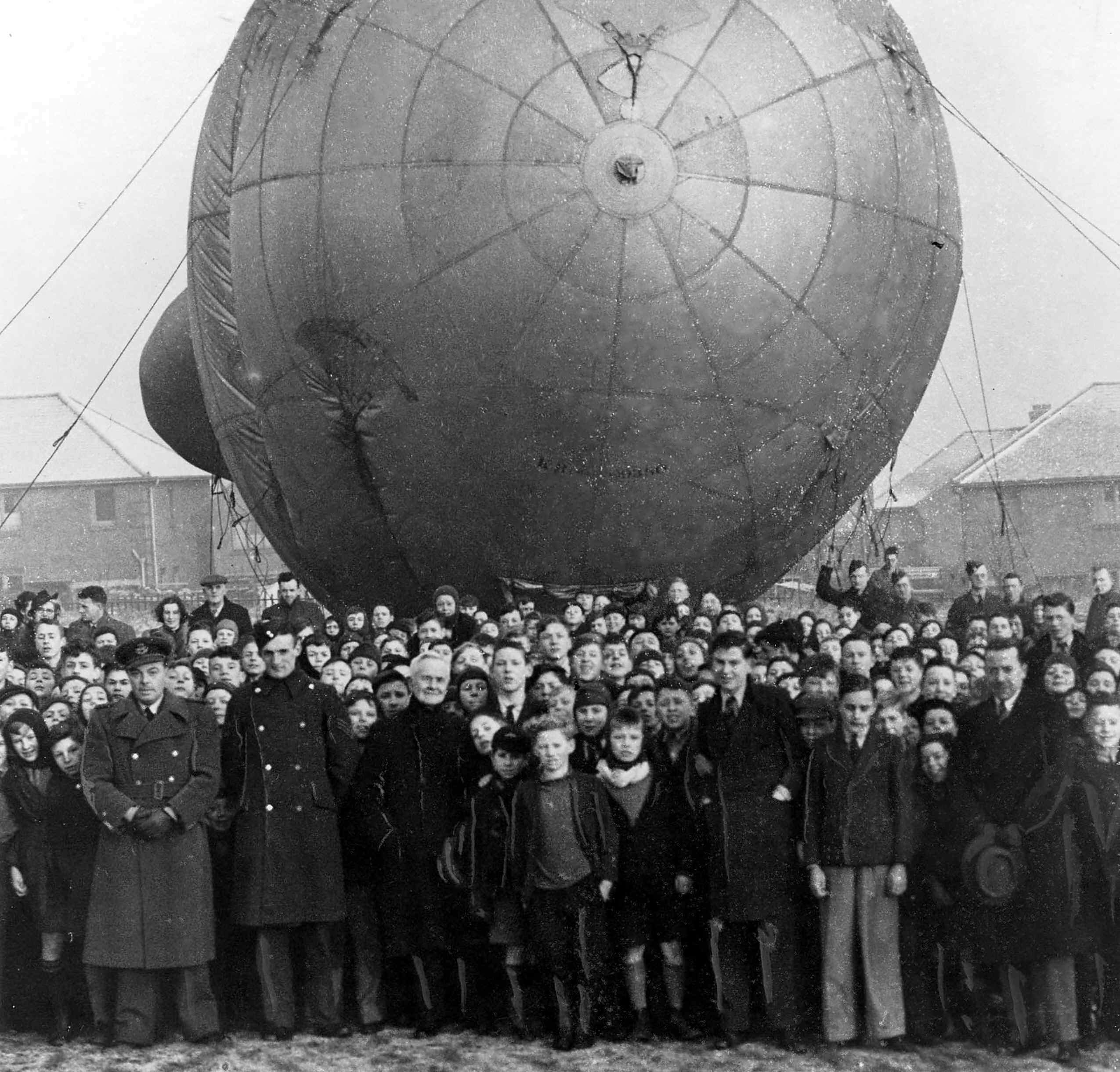

School

children from Bristnall Hall Senior Boys School pose with their local barrage

balloon which belonged to 911 Squadron. BirminghamLives

RAF barrage balloon personnel often shared in the civil defence role during and immediately after air raids. As

the threat of invasion grew, a number of industrial cities and towns were

divided up into various defensive sectors and in some of these it was the

balloon squadrons which took on command and control. Personnel were given

regular weapons training and, together with the Home Guard, were given specific

responsibilities for defence

in the face of enemy infiltrations on the ground. This meant close liaison not

only with the Garrison Commander, but also commanders of the Home Guard, both

Field Force and Factory Units.

A crew at work on a deflated balloon. A.B.Burr

Another role given to the RAF balloon squadrons was that of organising

and operating decoy fires. Carefully laid out trench systems containing petrol

could be ignited to simulate a town on fire when viewed from the air. These

Special Fires were first tried in late 1940. Subsequently they became known by

the codename ‘Starfish’ sites. In January 1941, all Starfish sites became

the responsibility of Balloon Command.

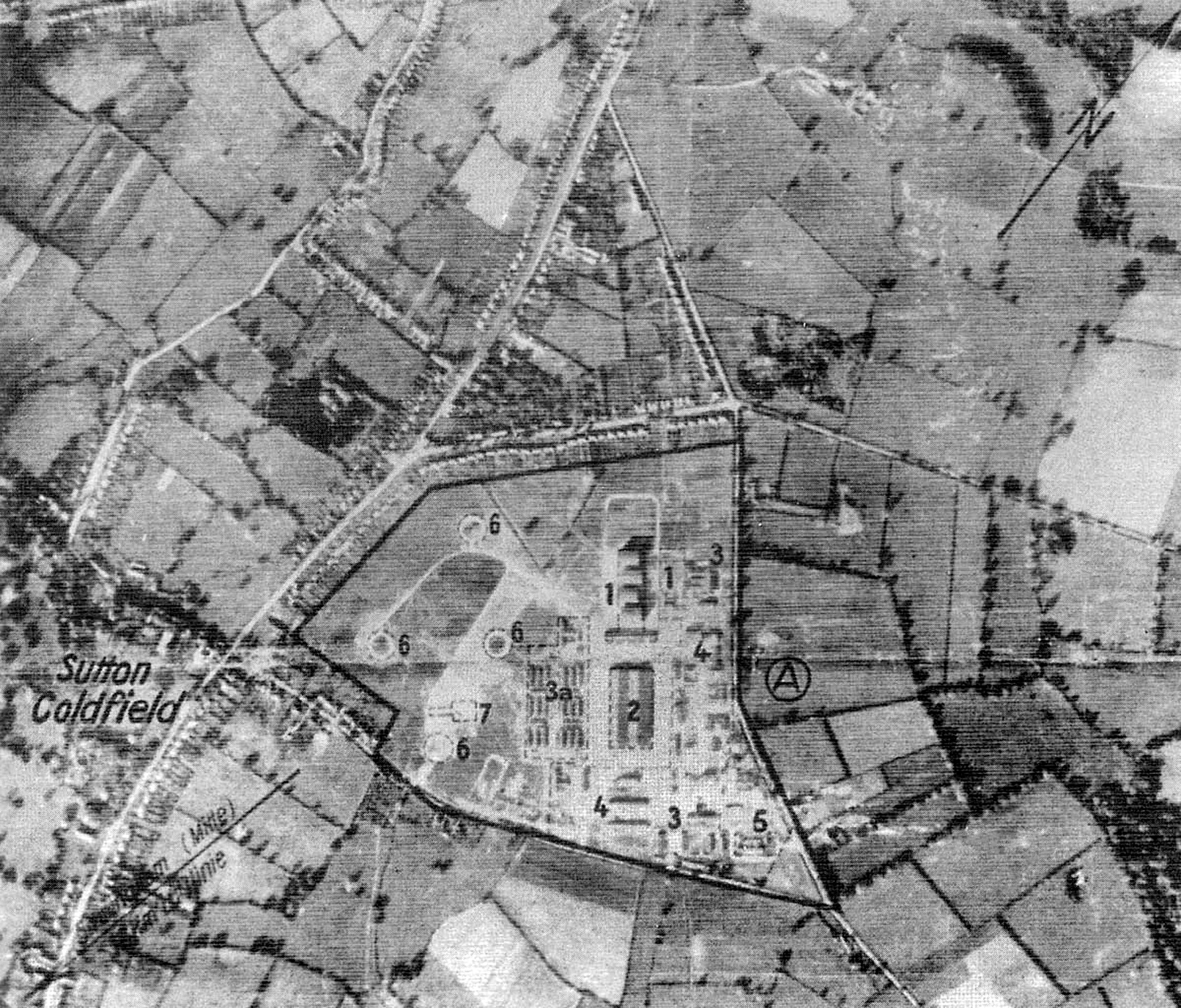

A German

reconnaissance photograph showing 5 Balloon Centre at Sutton Coldfield.

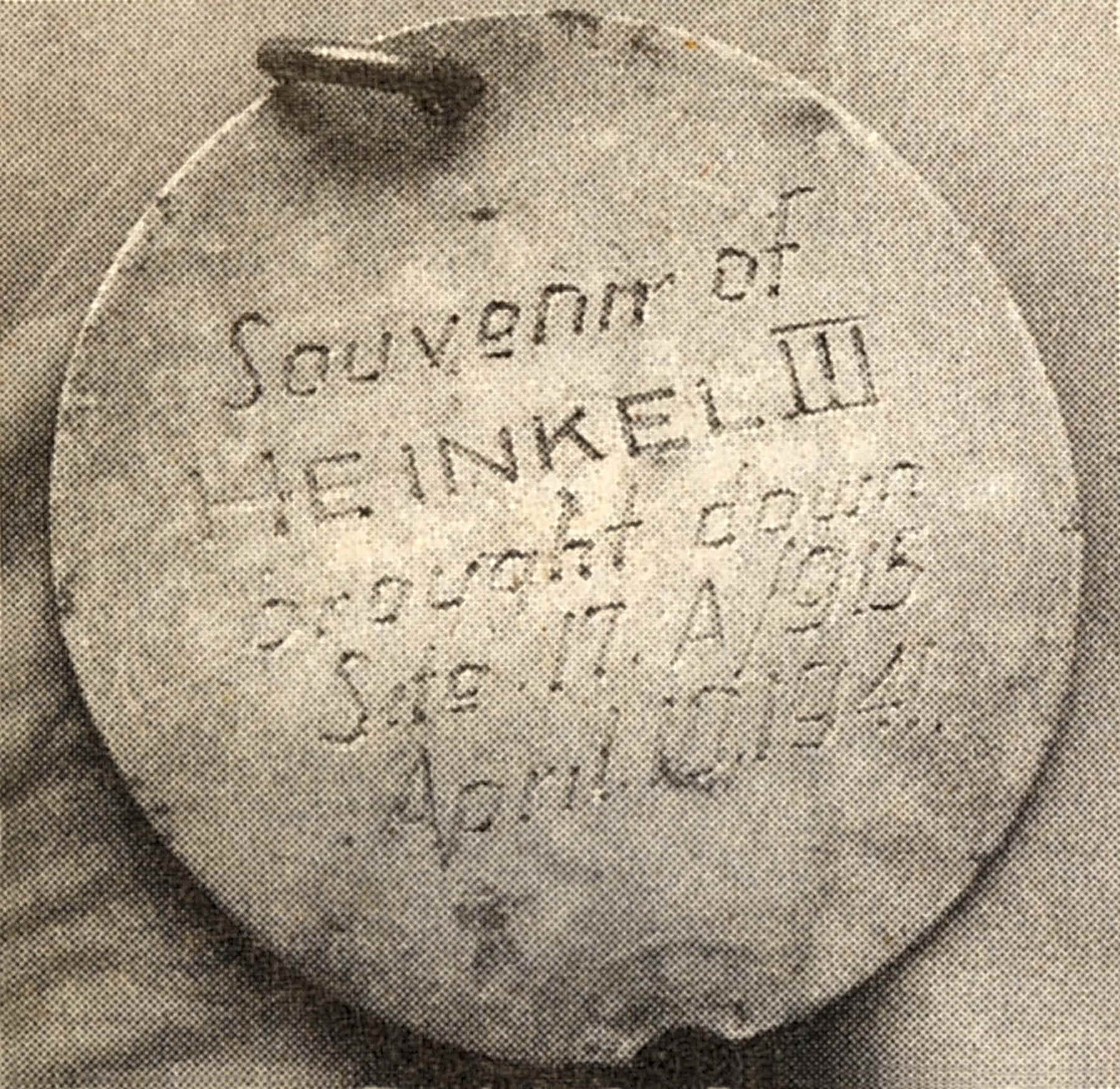

A

medallion, made from a piece of the Heinkel’s wreckage, was given to each of

the men from the Quinton balloon crew as a memento.

As the war progressed and the threat of air raids over the Midlands greatly

diminished, the Birmingham balloon squadrons were firstly merged and then

disbanded; so their hard-working personnel played no part in the victory parades

of May 1945.

Sidebar

Aircraft

which fell victim to Birmingham’s balloons

28th

August 1940

At 11:30 hours Miles Master I N7408 en-route

from Sealand to Brize Norton struck a balloon cable (site Pri 22 of 911 Sqn) at

West Bromwich. The aircraft crashed onto the roof of W & T Avery’s

factory, Smethwick. The pilot was killed but there were no serious civilian

casualties.

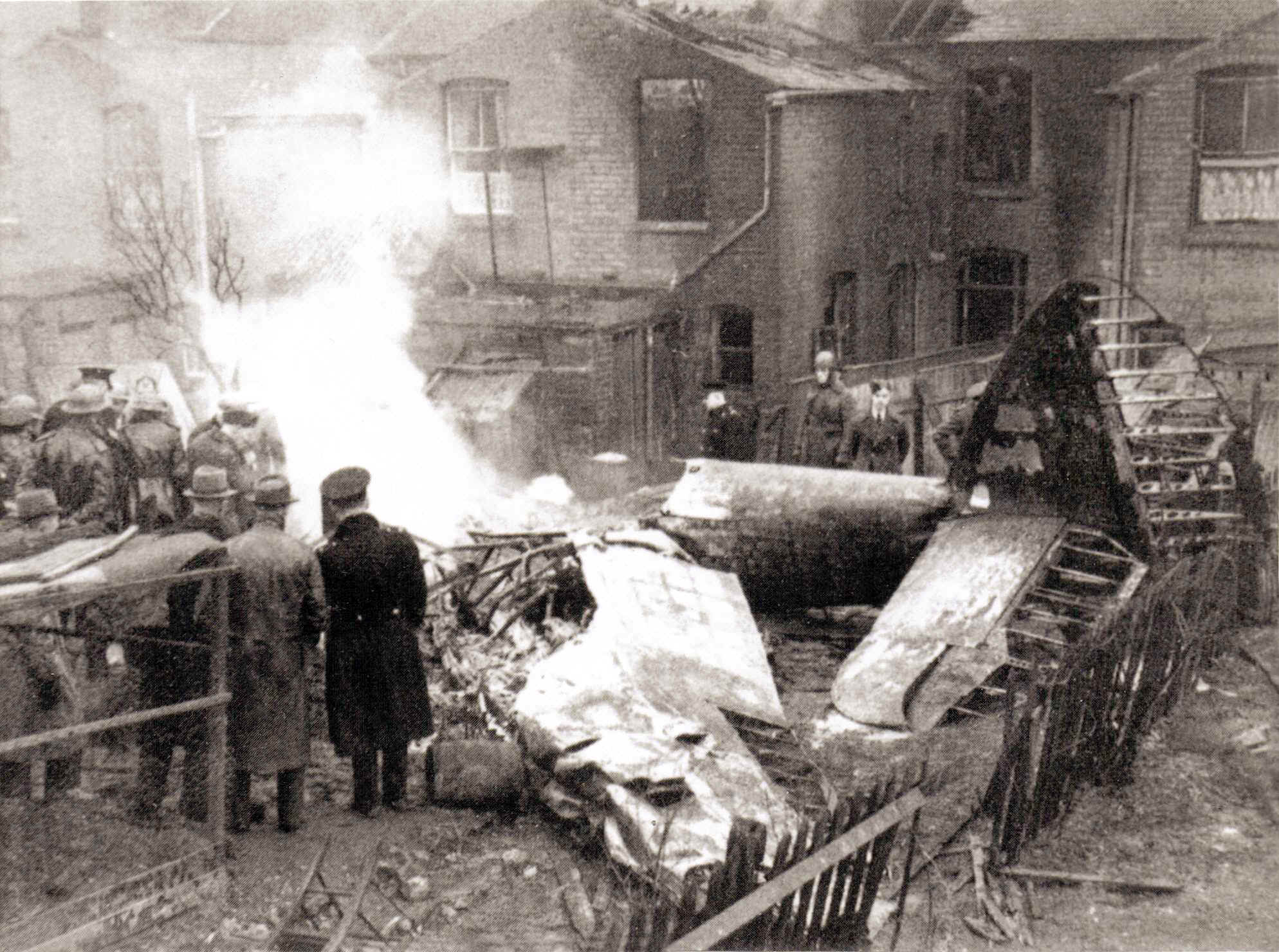

This wreck is an RAF Blenheim, which crashed at Bearwood on the

Birmingham boundary in February 1942. It collided with a balloon cable which was tethered at Avery’s sports ground in Edgbaston.

The crew of three was killed. BirminghamLives

28th

October 1940

Bristol Blenheim IV R3840 struck a balloon cable (site Pri 24 of 911 Sqn)

at 15:30, severing a wing. The aircraft crashed near the Warley Odeon. The

machine was being ferried by the Aircraft Transport Auxiliary (ATA) which was

based at White Waltham, Berkshire. The pilot was killed.

9th

November 1940 Avro

Anson I N9945 of the Wireless Intelligence Development Unit (WIDU), based

at Wyton, Huntingdonshire, hit a balloon cable (site 3 of 913 Sqn) at Stechford

and crashed onto the LMS railway track. The accident occurred at 00:15. The crew

of five were killed.

12th

December 1940 Hawker

Audax I K7445 of 9 FTS crashed at 16:30, after hitting a balloon cable (site 61

of 915 Sqn) at Longbridge. The pilot was killed.

12th

February 1941 Handley

Page Hampden I AD734 of 83 Sqn, based at Scampton, Lincolnshire, returning from

an operational mission to Bremen, hit a balloon cable (site 67 of 914 Sqn) at

02:06. All of the crew bailed out safely.

21st/22nd

March 1941 Bristol

Blenheim IV T1892 of 105 Sqn, based at Swanton Morley, Norfolk, whilst returning

from an operational mission, hit a balloon cable (site 61 of 915 Sqn) shortly

before midnight. It crashed soon afterwards at Cofton Hackett.

All of the crew were killed.

10th

April 1941

Heinkel He 111P (w/n 1555) 1G+KM of 4/KG27 was attacked by a Defiant and

then collided with a balloon cable (site 17 of 915 Sqn). The aircraft crashed

onto two adjacent houses in Smethwick at 01:40, killing seven civilians. Two of

the crew were killed and two were taken prisoner.

7th

July 1941

Armstrong Whitworth Whitley V Z6476 of 10 Operational Training Unit (OTU),

based at Abingdon, Oxfordshire, hit a balloon cable (site 51 of 915 Sqn) at

Quinton at 01:55. The aircraft was on a cross-country exercise. The Polish crew

of six were killed when the aircraft crashed on open ground at Quinton.

10th

October 1941

De Havilland Tiger Moth DH 82A T8199 of 19 EFTS, based at Sealand,

Flintshire, hit a balloon cable, stalled and crashed near Bartley Green at

12:40. The pilot was injured.

12th

October 1941

Westland Lysander IIIA V9612 of 7 AACU

hit a balloon cable (site 5 of 913 Sqn) at 12:13. It crashed at Erdington.

8th

November 1941 De

Havilland Tiger Moth II N9156 of 14 EFTS hit a balloon cable (site 29 of 913 Sqn)

at Castle Bromwich at 15:44. The aircraft broke in two and crashed a few hundred

yards from the balloon site, both of

the airmen having bailed out successfully.

20th

February 1942 At

10:38 a Bristol Blenheim IV Z5899 of 17 OTU, based at Upwood,

Cambridgeshire, hit one of 911 Sqn’s balloon cables which was tethered at

Avery’s sports ground in Edgbaston. It fell onto houses in Bearwood. There

were no civilian casualties but the crew of three were killed.

7th

August 1942

Vickers Wellington IC R1075 of 16 OTU, based at Upper Heyford,

Oxfordshire, hit two balloon cables in succession, site 12 at 01:37 and site 38

at 01:41 (both sites part of 911 Sqn). The aircraft crashed at Erdington. Four

of the crew were killed and two bailed out safely.

The author wishes to thank

Delwyn Griffith and Mark Evans

(www.aviationarchaeology.org.uk/marg/crashes.htm)

who supplied much of the information for this listing.

About the author

Steve Richards

became interested in aviation (particularly World War Two military) at the age

of 11 when he started building plastic kits of aircraft. In the 1970s-80s he

contributed large numbers of photographs and some articles to aviation magazines

and books. Most of his working life was in the darkroom side of photography. By

1990, his deteriorating eyesight had put a stop to this and early retirement

soon followed.

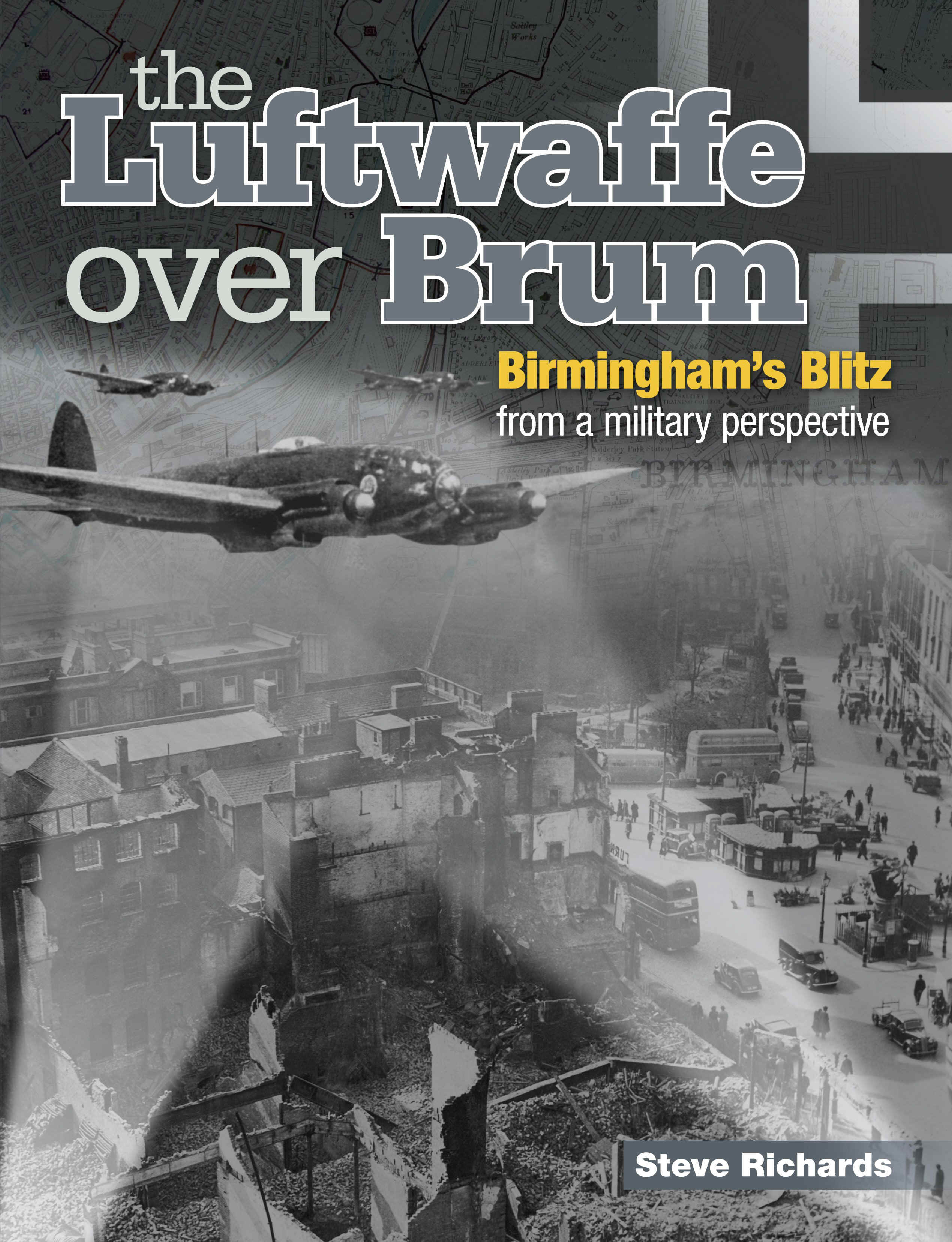

In 2012 he

commenced his most ambitious effort to date. Building upon his specialist

knowledge of Second World War aviation, he began work on The

Luftwaffe over Brum – Birmingham’s Blitz from a Military Perspective.

What is remarkable about this project is that by this time, Steve had no useful

sight and all the work was done using the eyes of friends and family to read

material for him, much of which had to be recorded onto audio. ‘Thank goodness

for voice recognition/speech software on my computer!’ he says.

The Luftwaffe over

Brum has been reprinted twice since it first appeared six years ago.

Steve is married with two grown-up daughters.

The

book costs £19.95 and is available from

Appendix

A - Who shot down the Smethwick Heinkel?

Until recently,

published information offered by local history groups concerning the Heinkel He

111 which crashed in Smethwick, credited its destruction to a Defiant aircraft

crew, Flt Lt Christopher Deanesly and his gunner Sgt W.J. Scott of 256 Sqn.

Two sources appear

to be at the heart of this claim: a dissertation which was written in 1994 by

local historian, Peter Kennedy, entitled The

Air Raids on Smethwick 1940-1942 and, secondly, an amazingly detailed work, The

Blitz Then and Now, volume 2,

published in 1988. Referring to the latter, there is a reference (page 520)

where Deanesly is cited as being responsible for bringing down the Heinkel which

then crashed onto houses in Hales Lane, Smethwick. Mention is made of the fact

that the RAF pilot was a ‘local’ Wolverhampton lad. It is, however, the

Kennedy work which, on the face of things, seems more authoritative.

Kennedy reproduces

what he describes as an extract from Deanesly’s flying logbook which tells of

the action against a Heinkel. Actually what he cites is a copy of the RAF combat

report submitted to Fighter Command HQ, RAF Stanmore.

The Smethwick

Heinkel came down in the early hours of 10th April 1941 at 01:40

hours. That Deanesly was in action over the Birmingham area on this date is

confirmed by the report and, indeed, by the squadron’s operational record

book. Crucially, his take-off time is recorded as being on the evening of the 10th

at 21:55 and his return to base was at 23:15. In other words Deanesly’s combat

took place on the night of 10/11th (not the early hours of the 10th).

On this night he brought down a Heinkel which crashed at Radway, Warwickshire.

It is to this combat that the report related by Kennedy refers, and is not

connected to the Smethwick Heinkel. In fact, 256 Sqn had no contact with enemy aircraft on the night of the

9/10th.

In later years two respected aviation historians, Christopher Shores and

Andrew Thomas, were each able to interview Deanesly on separate occasions and

inspect his flying logbook which showed that his first night victory was on the

10/11th April 1941. However, it is most likely that Deanesly was

under the misapprehension that his Heinkel had crashed at Smethwick. Apparently

the word through unofficial channels had reached him about a Heinkel going down

at Smethwick on the 10th and he, not knowing any different, seems to

have assumed this was his. Even the writer of the squadron's record book adds to

the confusion by mentioning a bomber down at Smethwick in connection with

Deanesly. The fact remains that the Heinkel which crashed at Smethwick had come

down 21 hours earlier.

The Defiant crew

who did, in fact, deliver the critical attack on the Heinkel were Sgt Harry

Bodien and gunner Sgt Dudley Jonas of 151 Sqn. This squadron put up a number of

aircraft in response to the large raid on Birmingham on the night of 9/10th.

Bodien took off at 01:10 and, following his engagement with a Heinkel, landed

again at 02:10. The Defiant’s gunner, believing his pilot to be dead, bailed

out after they had made three attacks on the enemy machine. Jonas saw the

Heinkel going down in flames and the impact as it hit the ground. Having

descended by parachute, he safely touched terra firma and was taken care of by E

Flight of 915 Sqn (barrage balloon). Here he was informed that reports were

coming in saying that a bomber had gone down on houses killing as many as 12

people.

On the 12th,

which was Easter Saturday, Bodien wrote to his sister who lived on the Isle of

Wight. He described in great detail how, in the early hours of the 10th,

he and Jonas brought down a Heinkel over Birmingham. His story mirrored his

formal combat report. Towards the close of his letter he wrote:

‘My gunner has

just got back and tells me our Heinkel crashed on some houses in Castle Bromwich

killing about 12 people. Hope the weather is good tonight.

Cheerio and all the

best,

Harry’

References to

Castle Bromwich and 12 people killed were inaccurate, but serve as an

illustration to how half-truths and rumour were rife in the heat of battle.

The Smethwick

Heinkel was the only German aircraft to crash onto houses in the West Midlands

during the war. Just one other came down in the immediate vicinity of Birmingham

and this was the Earlswood Heinkel which crashed in a field one month later.

H.E.

Bodien DFC DSO

Henry Erskin Bodien

was born in Hackney, East London, in 1916. The family called him ‘Snowball’

(on account of his white-blonde hair) or Harry but not Henry. It was while he

was an infant that the family moved to live on the Isle of Wight.

In September 1933,

he joined the RAF as an aircraft apprentice and trained as a fitter. He was

later accepted for pilot training and subsequently flew Avro Anson aircraft with

48 Sqn Coastal Command, on one occasion having to ditch in the English Channel.

In response to the

need for fighter pilots after the Battle of Britain, he transferred to 6 OTU at

Sutton Bridge, Lincolnshire, for conversion training to single-engine night

fighters. A posting to 151 Sqn followed. In May 1941 he received his commission

as a Pilot Officer. His biggest difficulty in securing officer status was the

need to raise £60 to pay for his uniform! He did this by obtaining a loan from

a relative. The rank of Flying Officer was soon attained.

In April 1942

‘Joe’ (the name which he picked up in the RAF) Bodien received his

Distinguished Flying Cross and one year later was promoted to Flight Lieutenant.

His career as a night fighter pilot was over; he had been credited with five

enemy aircraft destroyed and one damaged.

A period as a

flying instructor followed when he became a Squadron Leader. In February 1944

Bodien resumed operational flying, joining 21 Sqn as a Mosquito fighter-bomber

pilot. The Mosquito was a familiar type to him, as he had previously flown the

night fighter version with 151 Sqn. His second ‘gong’ was awarded in

September 1944 in the form of the Distinguished Service Order.

After the war was

over he stayed in the RAF, receiving various postings including duties in

Palestine, Rhodesia and Hong Kong and was attached to the United States Air

Force (1950-1951). With the USAF he flew in Korea, flying the B-26 Invader

aircraft on night interdiction sorties. He received a U.S. Air Medal.

On returning to the

RAF, Bodien then commanded 29 Sqn, which was flying Meteor NF11s from Tangmere.

This posting lasted from August 1951 through to June 1952.

In 1954 the Royal

Canadian Air Force was seeking pilots experienced in night interdiction to

assist in the setting up of its new Avro Canada CF-100 Canuck units. Along with

fellow night fighter ace Wg Cdr Bob Braham, Bodien transferred to the RCAF. He

was required to relinquish his then current rank of Wing Commander, dropping to

Squadron Leader for a period before being reinstated. Initially he served with

428 Sqn and then, in 1957, 410 Sqn where he regained the rank of Wing Commander.

Both of these squadrons flew the Canadian-built CF100.

Four years later in

1961, Bodien and his wife Phyllis became Canadian citizens. In that same year,

as part of the RCAF’s NATO commitment in Europe, he was posted to RCAF 1 Wing

at Marville in France, where he served as Chief Operations Officer. It was from

here that Wg Cdr Joe Bodien retired in 1965. The family returned to Canada, but

came back to Europe in 1970. Following a spell of touring, Bodien worked as a

civilian in Europe 1972-1978. Once again he moved back to his adopted home of

Canada, and after a few moves settled in British Colombia. Henry Erskine Bodien

died in 1999.

E.C.

Deanesly DFC

Edward Christopher

‘Jumbo’ Deanesly was born in 1910 in Wolverhampton. At the age of 27 he

joined the Auxiliary Air Force, flying with 605 ‘County of Warwick’ Sqn. He

received his commission in March 1937. Upon mobilisation in August 1939,

Deanesly soon found himself posted to a new Spitfire squadron, number 152. Twice

during the Battle of Britain he was shot down and had to be fished out of the

English Channel. On the credit side he part-shared in the destruction of two

German aircraft.

After the second

ditching there followed a spell in hospital and a short time as a Fighter

Controller. At the beginning of 1941 he was posted as a Flight Commander to one

of the new Defiant night fighter squadrons, number 256. During the spring of

that year, together with his gunner, a New Zealander named Scott, he brought

down four German bombers. For these actions Deanesly received the Distinguished

Flying Cross and Scott received the Distinguished Flying Medal (DFM).

In September he

became Commanding Officer. Further postings as a Commanding Officer followed

after April 1942, including duties in West Africa. Back in England he became

Chief Flying Instructor with 107 OTU at Leicester East. The unit was training

Dakota pilots for paratroop drops and glider towing duties. At the start of 1945

Deanesly found himself commanding 575 Sqn, which was flying Dakotas. The

one-time fighter pilot flew a Dakota glider tug in the Rhine Crossings of March

1945.

With the end of

hostilities, Deanesly was demobbed with the rank of Wing Commander. He returned

to civilian life and established a successful plastics company. At retirement he

lived in Edgbaston, Birmingham. Deanesly died in 1998.